25 Jun Sona Jobarteh

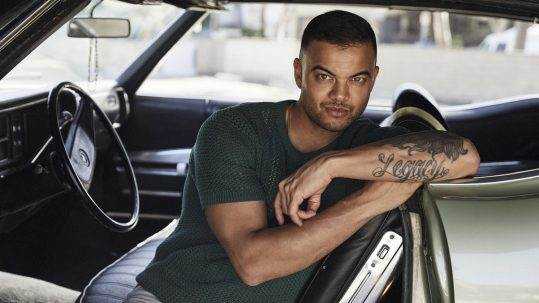

Photo by Anthony Griffin Photography

Sona Jobarteh

Raised in the UK and in The Gambia, Sona Jobarteh is the first female kora virtuoso coming from one of the main West-African griot families. Multi-instrumentalist, singer, and composer, Jobarteh is a leading force and an inspiration for other women to follow in her footsteps. Activist and very much involved in education, Jobarteh aims to create the very first African cultural institute in The Gambia.

By Victoria Adelaide | June 25. 2018

Victoria Adelaide: You come from a griot family. Can you explain what this means?

Sona Jobarteh: A griot family is one that is part of a very old tradition—a tradition that has been preserved for seven centuries. Certain music and instruments have been kept within griot families in West Africa. Today, griot families still play a very important role in West-African society, as they keep the griot tradition alive.

VA: You are the first professional female kora player coming from a griot family. What challenges did you face in the beginning?

SJ: When I started, I was a child; so, it wasn’t much of a problem. But once I became an adult, I encountered challenges. Initially, this music is for traditional events and social purposes, such as naming ceremonies, weddings, and so on. However, for the last few generations, this music has been played on stage to audiences rather than kept solely for its social purpose. This is what allowed me to find my place as a female kora player. If I had played the kora in its traditional cultural setting, it probably would not have been accepted. However, as I respected the restrictions imposed by the tradition and presented myself only on the stage—and I still only do that—, I could make the most of something new within the griot tradition.

VA: Some may wonder why the kora was a male instrument for so long.

SJ: Music in many societies in Africa is not separated from the function. It is something new to create music as entertainment. In olden times, this was not the case. You have to go back to when the griot tradition was established to understand its purpose. If you go back beyond the origin of the griot in its current state, which has to do with the Mali Empire, you go to the tradition that predated that, which was the hunter tradition. Over time, it gave rise to the griot tradition. Music had a role of protecting society, whose survival depended on the hunters, as they brought back food. This was a male job. Women were not involved—and still are not—in any acts of taking life, as they were regarded as the ones who bring life. So, as they didn’t want to bring bad spirits to women, men were responsible for taking life. But they couldn’t kill without taking care of the spirit of the animal they killed. Music was used to make sure the spirit was at peace and would not harm the community. This was done outside the community, in the bush, in deserted and inhabited areas in order to protect the community. This is where the origins of this male tradition began. Later, when it became associated with empire building, at the time of the Mali Empire, this continued. The griots were not just playing music in the royal court, they were going to the battlefield with the king. They were warriors. Women were not going to the battlefield. The griots encouraged, inspired, and gave power to the king. No king would go to war without his griot; every king had his griot. It’s only later when the tradition stopped being connected to warfare that it could evolve as entertainment. Now, women can take up the griot tradition because nobody goes to war and no one gets killed but the legacy of that male tradition is still alive today, even though society and the rules that were set have changed.

Photos from the WTO Aid for Trade Global Review 2017 – Photo: © WTO/Jay Louvion – CC BY-SA 2.0

VA: So your music carries a powerful message…

SJ: Everything that I do as a musician wouldn’t count for anything if I was not able to make a change in the community that gave birth to what I do. A major part of that is the females and young girls I have at my school who are studying the music and the tradition, as well as girls and boys who were not born into griot families—which is new. Society is changing. I try to remind people that the tradition must be kept up to date for it to survive because if we don’t, the tradition will be left behind. Nowadays, some of the griot tradition has become stagnant; griots only sing about things they will get praised for. The griots’ original role was to challenge society, to challenge the ones in power, to try to make people think about the issues they face every day. The music that I’m doing must always challenge those things and I want other griot musicians to remember that. What is also important is the education that we’re providing regarding underage marriage, FGM, and the oppression of women in so many ways. These are some of the issues we have to address and the only way for me to do that within the culture is to start talking about it through our music because everybody listens to music. Music goes through every single village in the whole country. This holds so much power.

VA: You grew up and were raised in London. How did it impact your perspectives?

SJ: It’s quite difficult to evaluate yourself based on two different identities. I only see myself as one person. I’m the sum of my upbringing, of my life. Experiences that I have been exposed to have a huge impact on the approach I have to my work. Having been able to have a good education in a culture that is different from African culture, as well as receiving a traditional education with music in Africa, I see it as a great advantage. So, I take the best from both worlds. Although my heart and my existence are very much on the African side, I still find myself consciously adopting approaches that I have been exposed to in Europe. I see many things that work and would be a huge benefit to the development of our society in Africa. People who are not of dual heritage, but have been raised or spent a lot of time in Europe, also come to Africa with so many new ideas. I would like to see more of the diaspora play a role in Africa’s social development. We need the expertise of those who know how to interface with some of the dominant powers in the world, which use so many means to control African countries. I think it will require a lot of people who understand how those systems work to come back to the countries and help develop them from the ground. The Gambia is a small country but, for me, it’s a perfect example of this. We really have so much to develop when it comes to infrastructure, management, and so on. We could learn so much from other communities around the world—not just Europe but from everywhere. All my travels through music have allowed me to see and be exposed to so many different cultures and settings from around the world. I definitely take all of that, all my experiences, bring it back, and try to implement it in ways that can be productive in the country.

VA: What are your ambitions for your school?

SJ: My ambition is to set up an institution in Africa that will preserve and provide resources on our culture for people within The Gambia. In the UK, at the university where I studied, they have an amazing library and a resource center on African culture. I see people from Africa and from all over the world traveling to the UK to study African culture, history, etc. People in Africa should be able to study on their own continent and we should have the same facilities rather than having them in Europe. Africa should be the first place to go to study African culture, not Europe. That’s how my dream to create the first cultural academy in The Gambia started. We need to have an institution in Africa that can deal with this kind of cultural propagation. My dream became stronger when I started teaching and sending my students for a few weeks or a month to The Gambia to study. In the UK, the level of study was amazing but when they arrived in The Gambia, the level dropped. Teachers didn’t show up and there was no professionalism. When I started, I knew I had to go one step at a time, starting with full-time school. Families want their children to have a good education and, unless I could offer all the educational aspects of the curriculum, not only music, I was not going to get the commitment of the students or their families. As a professional musician, you also need to have a good academic education to make your life easier. It really affects people’s confidence when they are dealing with low levels of literacy, no matter how amazing they are as a musician. Moving forward, again, the ultimate goal of this project is to be the first cultural academy in the country. We now have architects on board, the land is available, and the final plans are on the way. We have a special music department, which allows us to give training in music technology and music theory and a dance studio, which is the first in the country, where we can teach dance and develop the artistry of dance in the country. We have a library, which is also the first resource center where we are going to start documenting and housing all of our audio records from years of recordings done by both outsiders and people inside the country. It is a place where everybody can come to have access to the audio recordings of some of our great forefathers. We also want to include the sciences. In The Gambia, there is no facility for children and young people to study science. It’s something that is still underdeveloped in a lot of countries in West Africa, and we want to allow people to pursue science. This is a huge project where we will be moving in December 2018.

VA: You are working on a new album.

SJ: Yes, most of it is completed and my goal is to have the album finished by December 2018.

VA: You created a new instrument you named “nkora” for a film. Can you tell us about that?

SJ: This film was about the different areas of Africa. The challenge for me was to create a soundtrack that was not too rooted in West Africa, to try to create sounds that could not be recognized immediately by people from those cultures. Of course, the only way to do that was to create an instrument that was different. It’s a cross between a kora and the donso ngoni, which is the traditional hunter’s harp from Mali. With a mixture of the two, it is definitely something many people ask me about because they hear the instrument but can’t recognize it. So, it successfully creates confusion, which was my intention. The whole soundtrack was very much about trying to explore new ways of cinematic expression in African music—how we can create cinematic sound without having to default to Western instruments every time. So, that was the challenge of creating this soundtrack.

...Everything that I do as a musician wouldn’t count for anything if I was not able to make a change.``