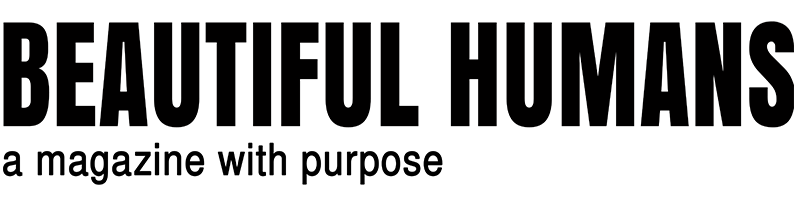

24 Mar Christian Sands

Photo by Anna Webber

Christian Sands

A piano prodigy and Grammy-Award nominee, Christian Sands started playing before he could even walk. He was enrolled in classical piano lessons at four, wrote his first composition at five, got into jazz at seven, and was a professional musician at ten. As a teenager, Sands was mentored by legendary jazz pianist and educator Dr. Billy Taylor, which ignited the development of a remarkable career, recording and touring internationally with Christian McBride’s Inside Straight and Trio, as well as collaborating with the likes of Gregory Porter and Ulysses Owens to name a few. Be Water, his third album for Mack Avenue Music Group, was released in 2020 and received critical acclaim. Sands was recognized by the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards where he was a nominee in the Best Instrumental Composition category for his composition Be Water II. Additionally, Be Water has been nominated in the Outstanding Instrumental Jazz Album category at the 52nd NAACP Image Awards, which will be held on March 27th.

By Victoria Adelaide | March 22. 2021

Victoria Adelaide: You started playing the piano when you were one, and at the age of four, you began classical piano lessons, and then at seven, you shifted to jazz. What made you switch from classical to jazz?

Christian Sands: I was playing classical music, and I love to improvise. So, I would improvise on all of the box suites, the Chopin or the Mozart that I was learning. My teacher was so upset with me, and she would say, “Don’t do that! Bach never soloed like that!” So after saying “no” so much, she told my parents that I should go into jazz because I liked to solo a lot. I was seven years old, and it took a second to find a jazz instructor who wanted to teach somebody so young, but I found one. I started studying with this amazing jazz pianist and composer, Rex Cadwallader. Studying with Rex was incredible.

VA: So you could express yourself freely.

CS: Yes, I found something where I could express myself freely without being told, “You can’t do that!” So, jazz was it for me.

VA: Since the beginning of your early career, you’ve been fortunate to work with some of the greatest musicians on the planet. One of them is Christian McBride. How did you meet?

CS: We met two different times. The first time I met him was my first year in New York City at the Manhattan School of Music. Jesse Simpson, a friend of mine at the time and a fantastic drummer and cymbal maker, told me that Christian McBride was doing this listening session, I think, at the National Jazz Museum in Harlem, or somewhere. He asked me if I wanted to go. So we got there. McBride was sitting in the middle of the room, and people sat around him on chairs. They were listening to Freddie Hubbard records, Miles records, and all this stuff. It was really cool. He was talking about the history of the music. So at the end of it, everybody’s going up and talking to him, and anybody who knows Christian McBride knows he is such a nice, warm guy and an amazing human being. So, we waited around, and then he looked at us, and he went, “Hey, you guys are musicians?” and I was like, “Yeah, Jesse is a drummer, and I’m a pianist.” So, he said, “Oh, so you play the piano!” And I replied, “Yeah,” and he went, “Well, why don’t you play something for me? There’s a piano right next to me.” So I sat down at the piano, and the piano was—horrible! The pedals didn’t work; there were missing keys, it was out of tune, and it looked like it had gone through the woodchipper. So I tried my best. I think I played Stella by Starlight, trying to make it sound really good. Given the circumstances, it was okay. He looked at me, and he was like, “Yeah… Okay.” (laughs) So, fast forward my junior year of college, I got a call from a few friends of mine that went to The Juilliard School. They were auditioning for a program that Christian McBride was running in Aspen. Initially, the pianist and composer Kris Bowers was supposed to be in that group, but he couldn’t do the rehearsal. So they asked me to do it. Then, I come to find out that for the band that auditioned, they wanted everyone in the band to go to the clinic. So we ended up going to Aspen. I met him again, and he remembered me, but it was hazy. I also met Ulysses Owens at the same time. I met them both there. We hung out, talked, and one thing led to another, a little session here, a little jam session there, talking about music, records, and so on. Then I had the opportunity to be on the Marian McPartland show, which was such an honor. Unfortunately, she was feeling ill, so she couldn’t make it, but she sent a substitute, and her substitute was none other than Christian McBride. We ended up doing Piano Jazz, the radio station, and I believe it was maybe a month after that; I got a phone call from his manager saying, “Hey, Christian McBride is playing at the Jazz Standard in New York for a week. Do you want to play?” I threw down all my homework instantly—because I was doing homework at the time (laughs). I said, “Absolutely, let’s get it!” I think that was right when his record Kind of Brown had come out. We ended up doing the Jazz Standard and touring, which led to the trio and to us being brothers now.

VA: Yes!! (smiles) Also, I feel that all these incredible musicians, especially in jazz, are profound thinkers, so, very often, the lessons we learn from them goes way beyond what we may expect. That must be incredible!

CS: Absolutely. It’s always been that journey. The first people I ever played with were Frank Wess and Clark Terry. I was seven years old. The fantastic thing about growing up in New Haven, Connecticut, is that New Haven is such a unique hub of art—because it’s right in between Boston and New York City. So everybody who’s got to go from New York to Boston has to go through New Haven, and go through Hartford—where Jackie McLean and Horace Silver were—or vice versa. Growing up in New Haven, I had the chance to experience a program created by some amazing musicians who would bring all of their musician friends to Yale University. One of the first jazz concerts I went to was Frank Wess, and I believe Renee Rosnes was playing. Actually, I think it was Renee, Frank Wess, and Clark Terry. I can’t remember who else was playing, I mean, I was seven (smiles), so I can’t really remember. So they do the concert, and then the next day, they do a masterclass, and you get a chance to play with them. So I ended up playing with them a lot. It was about playing with these masters and also listening to the stories they told or what they had to say about how to play well. Growing up, I always played with older musicians because I was always the youngest person (smiles). So, in my early career playing in New Haven, all the local guys were in their fifties or sixties. Many of them played with Mongo Santamaría, Lou Donaldson, Sonny Rollins, Jackie McLean or Nat Reeves, all these musicians that were around at that time. So I’m playing with those guys, they’re much older, they teach you—not exactly in words—but they teach you musically, like this is how the swing feels, this is how the shuffle feels. This is what we used to play with Lonnie Smith, back in the day when we were opening up for so-and-so, and you really feel that energy from these older musicians. Older musicians have always been a part of what I do. What I love about Christian McBride is that he’s very much the type of person where he’s coming straight from the Freddie Hubbard school, he is coming straight from all the people he’s worked with, and he brings these people in the Art Blakey school because that’s where Freddie was coming from—the Art Blakey stuff. Wynton Marsalis comes from Art Blakey as well. Ralph Peterson, bless his heart, bless his soul, Ralph Peterson—that was the Blakey school. So he’s groomed so many different musicians, and I strive to do the same thing; we all strive to do the same things like the people who came through that.

VA: As a youngster, you practiced martial arts and were immersed in the philosophy behind it. It feels like each of your albums is a reflection of the mindset you are in at the moment you write them. In Be Water, we can hear the voice of Bruce Lee inviting us to be like water. Ironically, Be Water was released in the middle of a global pandemic, and you had no idea when you wrote it, that indeed its entire concept on transformation, malleability, being more like water, would fit the current mood very much. How did all that inform the music you do now?

CS: Yes, all of it does. I write my experiences, what I’ve experienced, even if it’s not my own story. It could be the reaction to somebody else’s story as well. Be Water was just one of those moments where a lot was happening, emotionally, mentally, physically. I was in the process of moving, I had turned 30, and there’s such a dramatic difference between 29 and 30, at least for me. It was like there was more responsibility now. I went from being a bandleader to being a musical director and a creative ambassador; I am the head of things. I’m wearing certain hats. Responsibility is pressure, and then how do you cook under this pressure? It changes your style of leading. How do you navigate through things that you’re not really sure about? What does the future hold? How do you navigate to get there? I was quite a strategic person; I’m going to do this to do that. So, what I looked at was really how water does all of that. Water is everything, and it’s also nothing at the same time. When you think about people, about relationships with people and yourself in this world and the universe and how you affect everything, you are this molecule in the water. How big are you? How small are you? How malleable are you? Are you something that just gets beaten over with the waves? Or are you something that allows the waves to part, create something new, create rivers? There are so many different ways to approach it. So all of that was naturally happening during my year, traveling, performing, spending some time in Shanghai, in Hawaii. That was so beautiful. Changing my diet (laughs). I’m a naturalist. I love nature and being close to it. I grew up with birds and rain; I didn’t grow up in a city. Well, I did, but when I was very little, then we moved to the woods essentially. I grew up with deer and other animals coming into my backyard. I wanted to reconnect with that. That’s why you hear water and ice on the record. There are all these different properties of water. I wanted to include what I heard when I woke up in the morning or when I went to sleep at night.

VA: You work with so many musicians. When you start a project like Be Water, what makes you choose these particular players?

CS: A lot of it is being a fan of their art and how they present their work. Most of the people who are on the record are all band leaders. Marcus Strickland, for example, I admire where he’s come from. I admire his sound, especially the tenor saxophone sound; he’s got such a great tenor sound. Not many people have that type of old-school tenor, where it reminds you of Coleman Hawkins, Coltrane, Ben Webster, or Branford Marsalis at a certain point. It reminds you of tenor masters! Tenor—it’s still great, but there’s something about the lineage of how he plays the entire horn with the body and everything. It’s beautiful! I’ve always loved what he’s done. He’s also a good friend of mine. I admire his work and how he plays. The same thing goes for Sean Jones on the record or with Steve Davis. I know Steve for having worked with Chick Corea and with so many different musicians. We’ve taught at the same jazz programs in summers. He’s also my neighbor, and he’s very special. Ultimately I look for somebody who’s really special. I learned that from Dr. Billy Taylor. I would ask him, “How do you put bands together?” And he would say, “You gotta find somebody that does something really special for you, and find what it means to you.” So everyone I choose needs to have something special. Yasushi Nakamura, he’s such a fantastic human being, and his music comes out as that. He’s so receptive, he’s such a master at his instrument, and he represents such an amazing lineage of just bass playing and Japanese bass playing. He’s such an incredible beacon of this music and culture. So playing with him is incredible. Marvin Sewell, I fell in love with his playing back when he was playing with Cassandra Wilson. And I’ve always been a fan of his because he’s such a unique player. I heard Marvin so long ago that this is how I hear music; he is in my musical DNA. So when I got a chance to actually work with him, I said, “Hey man, you want to be on the record?” And he was like, “Yeah!” I was super ecstatic because it’s like being Kobe Bryant, and then you get to go over Michael Jordan’s house, and now you’re friends. You know, it’s like that, he made the way I hear things, how I approach things, the way I worked my chords… I get that from him. So, it’s really fun to work with him. And then he’s like, “Well, I got some stuff from you,” and we get the trade, you know! It’s such an amazing time to put bands together in a new unique way where it’s a bit like, “I’m a fan of yours, you’re a fan of mine; now let’s make something, and see what happens at the end.”

VA: That’s interesting. The other day, I was reading that 40-page guide-book Chick Corea wrote for musicians. He explained that when he chooses musicians to play with him, he always gives them the necessary space to express themselves and let their uniqueness shine.

CS: Absolutely! Watching Dr. Billy Taylor work—and at the time, it was Chip Jackson on bass and Winard Harper on drums—it’s not just that the music is swinging; it’s amazing to watch as well. Dr. Billy Taylor is playing, then you got Chip who’s doing some stuff that I’ve never seen a bass player do. Winard has this thing where he does a cymbal grab, where he just gets off the drums, and the way he plays it is such a beautiful thing. So to watch them and to watch Dr. Taylor allow them to express themselves within the construct of the song or the set, it’s incredible. When you watch certain people like Monty Alexander, for example, Monty is the ultimate performer, entertainer, musician—God! Monty is so awesome. The music is swinging, and when you listen to the records, it’s killing. It’s coming out of the Gene Harris, coming out of the Oscar Peterson and coming out of the Art Tatum. But it’s also to watch him and then watch what he does with his musicians and who he picks. Like with Obed Calvaire, I can understand why Monty chose Obed. There are a lot of great drummers out there, but Obed is so special. It’s just like Chick with Marcus Gilmore. Marcus Gilmore is so unique, and it worked with Chick. I love certain combinations of people. I love listening to certain pairings like Gonzalo Rubalcaba and Charlie Haden and then hearing the same song with Brad Mehldau playing with Charlie Haden. And how does that work? Who’s bringing something to this, and how do they play against each other? There’s a similar fabric that’s there, but there’s also the uniqueness of this person who does this really well. Clark Terry and Oscar Peterson, that’s the perfect example of high-level swing, and then there’s Ray Brown, all those cats, the way they play together, they understand each other at the same time, but they’re also bringing so much that’s affecting each other too. They’re bringing this fun, and they’re bringing this groove, and it’s incredible. So I try to do that with the people I choose.

Photo by Anna Webber.

VA: If I ask you to name three pianists that have inspired you tremendously, who would they be?

CS: Hmmm, that’s hard….Well, I’d say, Art Tatum, Gonzalo Rubalcaba, and Jason Moran.

VA: I saw that you also have a web series, the Sands Box, which is a collaboration with the Monterey Jazz Festival. You interviewed quite a number of jazz musicians, including Jason Moran.

CS: Yes, I studied with Jason when I was in college, and it’s always great to pick his brain on something because I love the way he thinks. I wanted to do an episode about African-American excellence, Black excellence, and Black Art, specifically hip hop and jazz—because that has been one of the most important cultural movements in America and the world that other people understand. So talking about putting bands and people together and getting Ali Shaheed from “A Tribe Called Quest” and Jason Moran was perfect. Ali is a DJ, and he is such a historian with the music; he knows records, and he knows just a pile of this information. Then there’s Jason, who I say is a sort of piano DJ, because of how he puts things together—it’s very much how a DJ would chop things up, moving things here and there. At the chance of having them together, I was like, “Let’s do that, let’s have that conversation.”

VA: A few months ago, you collaborated with Ancestry and discovered you had roots in Cape Verde. How has that impacted you?

CS: It had already influenced me in the way of just curiosity, finding the lineage of things. I was playing before and, I didn’t think anything was necessarily missing, but if you asked me where my great, great, great, great, great grandfather was from, I’d have to guess. I didn’t know. So, after finding out, I was like, “Okay, there’s a place now, especially for African-Americans in America.” We don’t know where we’re from. We assume Africa, and we want to say that, but it could be the Dominican Republic, it could be Haiti—you have no idea because of American slavery. To learn that my fifth great grandfather was from Cape Verde is incredible because now there’s a pin there. Then to discover his life’s achievements was equally inspiring. He was a musician, a flutist, a composer; he traveled to Maine and not as a slave. He started the first brass band in Portland, Maine. He also had a business at the height of slavery. He was a barber and an abolitionist; he fought against slavery and established one of the first underground railroad points. When I think about this impact he had on American history and human history, that really affects how I approach my music, what I write about—it affects what I say. Especially within last year, and what was politically happening in America—this is something that’s happened forever. But to be more vocal about it, to be more involved about it, to have more conversations with other people about it, to create this narrative now, it has been inspiring just from learning that. So at this point, it’s affected everything, and then we share the same name: His name was Christian too, which I didn’t know.

VA: You were a nominee at the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards, which were held last week, and you are also a nominee at the 52nd NAACP Image Awards, which will be held in the coming weekend. How does it feel?

CS: I was thrilled! That’s a great honor, being nominated at the Grammy Awards, and I’m looking forward to the 52nd NAACP Image Awards this week. It’s such a great feeling to be recognized for a project, especially during a worldwide pandemic, when so many people are focused on different things.

VA: We are currently in a global crisis with Covid-19. How did that affect you and your creativity?

CS: It was overwhelming because, on one hand, it’s a blank slate, so you can do anything, but at the same time, it’s anything. You don’t know if it will work and you need it to work, because performances are gone now. So what do you do? I am a performer. I love being on stage, meeting my fans and my audience. I identify with that. I’m also a bit of a private person; after a performance, I’m in my hotel room. I’d go out every once in a while, but I very much keep to myself. So I started the Sands Box series, and on Instagram, I was doing a Friday breakdown on Errol Garner’s music. I’m more involved in social media now because we need to interact with one another. As a result, there’s more for me to do now; I’m about more than just playing the piano as this artist. My artistry has expanded and not necessarily in the way that I thought or wanted to, but again—be water. You have to be open, and you have to go with it. But I’m not going to lie; it was very stressful.

VA: Any last words for our readers?

CS: Be kind, be honest with one another—love one another. We need more of that, especially now—love and patience. The world is gone to shit, as we say, but there are rays of light everywhere. Look for that light in your friends, in your family, in strangers and people. We’re not done. We have a lot of work to do. This is just the beginning of us improving the human race, and we have to continue to do that.

...It was about playing with these masters and also listening to the stories they told or what they had to say about how to play well.``