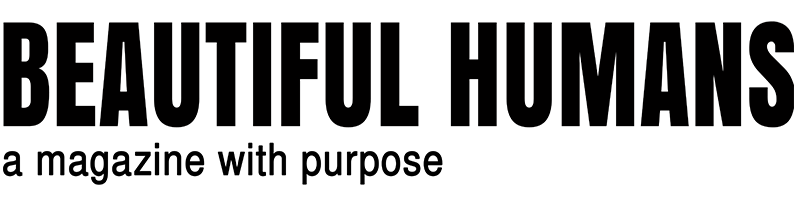

17 Dec Omar Sosa

Photo by Massimo Mantovani

Omar Sosa

A prolific musician, with a career that has spanned more than two decades, legendary Cuban jazz pianist and composer Omar Sosa has just released his thirtieth album, Aguas, in collaboration with vocalist-violinist Yilian Cañizares. Well known for his mastery at combining genres and various musical influences into jazz, Omar Sosa’s music is a reflection of the man himself—it is warm, welcoming, open to the world, and an invitation to greatness where the only currency is love.

By Victoria Adelaide | Dec 17. 2018

Victoria Adelaide: Mr. Sosa, what was your dream as a little boy?

Omar Sosa: My dream was to be a basketball player. I was living close to my school and teachers used to tell me, “You are tall; you could be a great basketball player.” Then I also wanted to be a dancer. Every Sunday, my father had a big party. We listened to Count Basie, Glenn Miller, and Nat King Cole. Music was part of my life because I could hear it at home. I remember when my father put on a record of traditional Cuban folk music, like Santería, I told him that I’d love to be a dancer, just for the pleasure of dancing to this music. Nowadays, when I’m in concerts, I dance. I like to dance to traditional folk music, especially African music.

VA: You said, “I’m not a jazz musician because I play that style of music; I’m a jazz musician considering the philosophic aspect of jazz. Jazz is freedom and, when you have freedom, you’re not tied to anything: everything is welcomed inside jazz.” What does freedom mean to you?

OS: It’s simple. When we have the opportunity to incorporate our inner voice in our creative process, and all the things that we hear around us, that we live or experience when we travel, it’s a gift. Jazz provides the potential of incorporating every single sound in the music, but we need to know the tradition. It’s not like making a collage. (laughs) It’s easy to put things together but what’s important is to understand the tradition and to combine this tradition through jazz to create one voice that can be a multicultural voice.

VA: You mixed genres, jazz, soul, African music, and even flamenco, on one of your previous records. You live in Spain; how did it influence you as a person and your music?

OS: Well, the way it inspired me comes out more in the food and wine areas. (laughs) It’s true that flamenco is mighty. However, for me, flamenco is an extension of Arabic music. The Moors were in Spain for about five hundred years, and when you listen to flamenco, the first thing you hear is the melisma of the Arabic melody. On my record, ILÉ, I had the opportunity to work with the great flamenco singer José “El Salao” Martín on several tracks, which was a great experience. Flamenco has a solid rhythm, Arabic influences as I said, and it’s all about integration, combination, and sharing. I love this music because of that. Today, flamenco is broadening, with singers like Rosalia taking it into pop and Americanizing it. It’s all about living in the moment.

VA: You surround yourself with musicians from all over the world and, often, you have to speak a foreign language with them. Do we think differently when we speak another language?

OS: The more languages we speak, the more information we feed our brain and our thoughts are processed faster. Through language, we meet people and we discover new cultures and new traditions. Then if we learn from those different cultures and traditions, we can expand our horizon, think as a global person, and become a multicultural person. When we are multicultural, we are better human beings because we are more tolerant. (smiles) Also, all those things help us in our creative process, whether it’s about writing a book or writing music. If I go to Morocco, I can speak with the people, then they invite me to their house, I eat with them, and it’s the same in other places in Africa, Europe, or Japan. Speaking languages should be a norm—something that comes naturally.

VA: Yes, I know Morocco very well. I really enjoy their local music called Gnawa. It’s very different from the music you can hear in the Middle East.

OS: The connection between Gnawa music and music from the Santería, Candomblé, and Voodoo traditions is very close. The Mluk, or deities of the Gnawa tradition, correspond to the Orishas in our Cuban tradition. In the Middle East, the music they play is different. It is darker, sadder, and more melancholic while Gnawa is happy music.

VA: You speak fondly of Cuba and how the less affluent people would still give you their best and everything they have if they can. A study showed that less affluent people have more empathy while richer people don’t. Do you think earning more means caring less?

OS: The more we have, the more we need to protect. The less we have, the less we have to protect, because the only thing we’ve got is our soul and happiness. Rich people always want more, then they need to figure out how to protect what they have. So, they permanently live with the fear of losing their possessions and, most of the time, they don’t even know who their friends are. I like this quote that says, “The richest person is the person who needs the least.” If we are not seeking too many things to be happy, we can enjoy the moment, relax, and be free from the burden of carrying too many responsibilities. Unfortunately, we live in a world based on money. We must start to think differently, because if we can live with less, then we don’t need to worry about too many things.

VA: I lived in Chile for a while and I noticed that the approach songwriters took to structuring a song was different from the way songwriters would do it in France, England, or North America. What has working with all those different artists taught you?

OS: That’s simple—rhythm and melody. To me, it’s fundamental because through rhythm and melody we know the tradition of the place. Lyrics come later, or in the beginning, depending on the composer. That’s what drives me in my creative process. Music is rhythm and melody—that’s it.

VA: Can you tell me about your collaboration with Yilian Cañizares?

OS: She opened for one of my concerts in the South of France five years ago. I really fell in love with her stage presence, her voice, her approach to melodies and rhythm, and the way she plays the violin while singing. So, after the concert, I went backstage to introduce myself. I told her I hope one day we could do something together because I really like the way she expresses herself. Two weeks later, I invited her and her family to eat at my house to see if the energy between us was good. Music is a notation of rhythm, but the fundamental thing in music and for me is the energy—the energy we present. Two months later, we went to the studio and we recorded the album, Aguas. It was natural and organic. This is the way I love things to unfold when everything goes naturally, when there is no pressure.

VA: What are you working on right now?

OS: There are two projects. First, we hope to release a live recording of the concert that Yilian Cañizares and I did—in a trio with Venezuelan percussionist Gustavo Ovalles—at Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg and at the Barbican in London this past November. Then, we have a new record that will be released late next year or early 2020 called Badzimo. It’s a recording we did with a wonderful South-African percussionist, singer, and composer, Azah, based on the folkloric traditions of the Limpopo region in the north of the country, using traditional Venda drums and flutes. This album will introduce a special South-African singer named Indwe. The project is in cooperation with Makotopong Sound Studios in Pretoria.

VA: What’s your biggest achievement?

OS: Being happy! (smiles)

...Jazz provides the potential of incorporating every single sound in the music, but we need to know the tradition.``