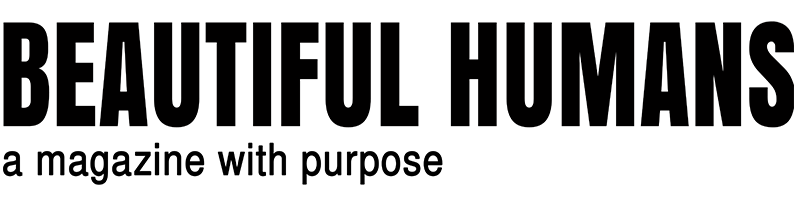

30 Apr Grethe Barrett Holby

Photo by Sophie Elgort

Grethe Barrett Holby

Producer, choreographer, dramaturge, and founding director of Ardea Arts/Family Opera Initiative—a company dedicated to creating new works of music-theater and opera to entertain, enchant, and inspire today’s multi-generational audiences, as well as engaging communities in the process and performance of the work—, Grethe Barrett Holby is a woman of many interests and of many talents. A visionary often ahead of her time, Holby is the mastermind behind the basketball opera “BOUNCE.” Through her extensive and pioneering body of work, Holby ignites a dialogue and creates positive, lasting changes in people’s lives.

By Victoria Adelaide | April 30. 2018

Victoria Adelaide: You have a master’s degree in architecture. How did it impact your vision of doing choreography?

Grethe Barrett Holby: I never really wanted to be an architect. I only wanted to be a dancer and to be in the theater. However, in America, as you might know, there is a lot of pressure to attend college. So, my parents said, “Off to school you go!” And off I went. I had been dancing professionally for a year in Norway before that. My parents suggested that architecture might be a good, secure job that ignites my artistic nature. So, I looked at schools, and when I found the program at MIT, it sounded exciting because then, maybe instead of designing buildings, I could design underwater cities and space stations. I have to say that MIT is one of the most creative places in the whole world. It’s not just about learning the sciences, math, and physics; it’s also a research institution and part of their concept is that new ideas can come from anyone—from a freshman or from the oldest person on staff. It’s not the kind of institution where you study first and then they finally bring you into a lab. It’s open to whatever you’d like to do in addition to the work you have to do, obviously. Right away, I started a dance company and planned a dance performance. It was the first piece I ever choreographed because, until then, I had been a dancer and had never thought about making my own work. It was in a laser beam sculpture that I designed and the dancers moved through the sculptures, changing it with their movements. It was way ahead of its time and the idea of being in a place where this could happen opened up worlds for me. So architecture became not only about buildings. It became a medium for creativity—the thought behind it—for example, the thought behind building a space station before there were space stations, underwater cities etc. I also studied naval architecture, oceanography, I went straight back into the arts and, through architecture, I started to study. I cross-registered at Harvard and I took set design from Franco Colavecchia, a famous set designer from England now living in the USA. I became involved in the theater in multiples ways. I was not only dancing—I was choreographing, I was in set design, and we also had to paint the sets. I got this entire idea of what the theater is, not only from the point of view of the director or the choreographer. And, in the end, you realize that anything is possible.

Photo by Sophie Elgort.

VA: Do you think one needs to have a certain mindset to succeed?

GBH: As we all know, women did not receive the same opportunities as men, especially back then. My mother was a Norwegian immigrant. She came over after the war, she worked in the Norwegian underground, and she was taken by the Nazis. She was a survivor and she just kept going. I think the way you are brought up has a lot to do with your mindset. She never said, “You can’t do that because you are a woman” or “Girls don’t do that.” Also, I spent one year in an all-girls school, Bryn Mawr College. It was the first time I really spent a lot of time with women, as most of my friends had always been guys. I realized women are terrific collaborators. And then, of course, I transferred to The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, what was essentially a boys’ school back then, where there were only 200 women and 6000 men. I think both of those experiences were unique and that I learned a lot. However, my mother had a lot to do with the mindset I grew up to have.

VA: How do you deal with the weight of tradition that a lot of people put on opera?

GBH: I didn’t come from opera. I came from dance and theater. Dance and theater always have something new and you’re always making something new. I fell into this extraordinary field called opera. My first two big experiences were new opera. And, thinking about that, no one was ready for “Einstein on the Beach”, no one was ready for Philip Glass or for Bob (Robert) Wilson, and they put a huge cast and crew together and were able to tour Europe and came back to New York with two performances at the Metropolitan Opera house. When I started making new work in opera, I did it because I felt as though opera needed to have a “Nutcracker”, because it doesn’t have anything to grab on to and to bring you into the art form. It used to be one of the most popular art forms—people were singing opera on the streets of Italy. Here we sing musical theater songs and rock. So, why aren’t we using our music in opera? I’ve been fighting an uphill battle since the beginning. I started the American Opera Projects back in 1987-88. I realized you need to have something that’s going to reach out to a large audience. It has to appeal and it has to enchant and entertain while being challenging and inspiring. Personally, I want to make new work that makes us see the world with new eyes. I don’t want to do something that’s depressing. We can deal with difficult subjects, but there has to be a positive message, as with the basketball opera.

VA: Let’s talk about “BOUNCE,” the basketball opera…

GBH: Well, the point is, how do you bounce back? That’s why it’s called “BOUNCE”. How do you bounce back from traumatic experiences and how do the rest of us start a national conversation? I’m not in a situation where I may get shot, but some people are. Middle-class people, who are integrated into the better part of the system of the United States, suddenly have their kids being shot at school. In underprivileged neighborhoods, those things have been going on for decades. I think it’s time for a dialogue and to bring people together over common situations that now impact all America. BOUNCE can speak to all audiences and, guess what, it’s on a basketball court! And what does everyone in America do and love? Basketball! It doesn’t matter if you’re in a bad situation or a good situation, you love basketball. So it brings people together to then share a story to start a dialogue. I think it’s incredible. I didn’t write or compose the piece, I just had the idea, brought the creators together, and they did an incredible job.

VA: Through your pioneering and innovative work you help people to make positive, lasting changes in their lives. How has the feedback been so far?

GBH: First of all, I have to say, I know it changed some lives because I’ve been told. But it’s not a one-way street. Everyone involved with the show, especially myself, has changed. It’s phenomenal because it’s all you need to do – to reach out to people you don’t know, people you would have never worked with. And, suddenly, we’re working together towards the same goal and any differences disappear. What opened my eyes was when I asked a teacher at the school in Bushwick—where the education system throws the kids they don’t know what to do with—“Why aren’t some of the kids who signed up for the show involved?” And she said, “You don’t understand; these kids had never ever gotten the opportunity. So, for them taking an opportunity is very risky. They don’t know what’s on the other side; they don’t know what will happen if they fail or what will happen if they succeed.” Frankly, I got inspired to start BOUNCE, after I read a book on basketball to my son. In the book, the basketball player is asked, “Why did you lose?” He replies, “Coach, anyone can lose” and the coach said back to the basketball player, “No, you lost because you were afraid to win.” And that’s what I’m coming across with so many of the people that we reached out to and who have been a part of this piece. It’s very scary for them – and for me – because if they/I win, then what? Maybe it’s easier to lose because that’s what they’re used to. These kids have this opportunity and it opens up doors for them. They may not go into the theater but it opens their eyes and they start thinking that if they can do this, then maybe they can do anything.

Photo 1 by Aaron Purkey | Photo 2 by Arthur Elgort.

VA: How long does it take to create an opera like this one?

GBH: It took me 14 years before I found someone that believed in this project. And that man, Torrie Allen, was able to open certain doors. One main thing he did was to bring Dr. Everett McCorvey from the University of Kentucky opera theater. Because the University of Kentucky is a basketball powerhouse, everyone there knows basketball even if they are in the opera department. So they were like, “Wait a minute, there’s an opera on basketball and we are not involved? We have to be involved. We are the basketball Mecca of the universe!” Without Dr. McCorvey, it would have been very hard. I have some wonderful people in my life as friends and in my professional life. They stick by me no matter what. You can’t do it without a group of people who believe in you. I’ve been very lucky. Without them, I wouldn’t be able to do any of this.

VA: You are also the mastermind behind Ardea Arts…

GBH: Yes, Ardea Arts, is the company producing “BOUNCE” and all my work now. I am the founding director. Ardea Arts will be 12 years old this June.

VA: You’ve worked with a myriad of incredible artists. What was your most memorable collaboration and why?

GBH: I’d like to share my Leonard Bernstein’s story. Leonard Bernstein was not only a great composer but he was a man of the theater. He never tried to tell other people what to do. Instead, he would describe what to achieve. I remember one particular time when I was sitting there with the lighting designer, Lenny was there and said, “No, no, that light cue is all wrong.” The lighting designer said, “This has to be lit here and there,” then he said, “You have to understand this is the only clear moment; this is the central moment of the entire opera. Everything comes together; everything is clear. Suddenly, it resonates with everyone before it all falls apart again and people go their own ways.” It was such a beautiful way of asking people to understand where we were and what they had to achieve. Much better than telling them how to do it.

Also, I worked with a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, Yusel Komunyakaa, as a writer on one of my operas still in development, called “The Three Astronauts”—it is based on a book by Umberto Eco and Eugenio Carmi. Yusef would listen and listen, then he would start writing all night. At about 6 or 7 am, I couldn’t wait to discover the email with the most extraordinary lyrics—I mean, in depth and in the beauty of the words. And it’s an example, perhaps, that I did learn something from Lenny because I wouldn’t tell him what to do. He was part of the story, making the story, and then he would go away and make it one thousand times better than where we had left it before.

VA: You have a fantastic modeling career. Can you tell us about that?

GBH: Well, that was only because I was making $75 a week dancing. My sister was a famous model; her name is Clotilde. She was the first contract model ever and she worked for all the greats. I’m not really tall enough to be a model. (laughs) I’m not interested in fashion, but one day Clotilde said to me, “Grethe, come on, you’re making $75 a week. Why don’t I just introduce you to Eileen Ford? And even if you work once a month, you will be making a few thousand dollars in order to support your dancing because, at the moment, you are barely supporting yourself.” She was the one who introduced me to Eileen. I was already 31 and Eileen asked, “How tall are you?” I said, “5 foot 7.” She said, “No, you’re not! But ok, we’ll say you’re 5 foot 7.” Then she said, “How old are you?” and I said, “31.” She said, “No, now you will be 26” and I said, “Ok.” Then she said, “Good luck, I hope I like your choreography more than my nephew’s,” and I said, “Who is your nephew?” and she said “William Forsythe.” It was a very famous choreographer and I said, “Thank you very much.” I was able to work for a living and support American Opera Projects, support myself, and support the work that I was doing. I owe her a lot for taking me on.

VA: You are now part of the Iconic Focus Models family…

GBH: Yes, all the women, Patty Sicular, Lori Modugno, and Jill Cohen Perlman are fantastic. Patty Sicular was my booker at Ford Models, and she has been terrific to me all these years, keeping me in the loop and supporting all my work.

Mrs. Grethe Barrett Holby is represented by Iconic Focus Models.

...I want to make new work that makes us see the world with new eyes.``