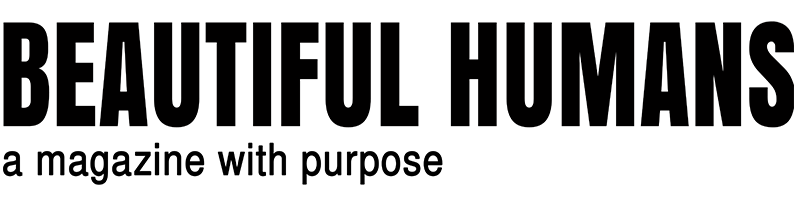

18 Jan Scott Neeson: A True Hero!

Photo: Christian Berg Photography.

SCOTT NEESON

From the high life of Hollywood to the Steung Meanchey garbage dump on the outskirts of Phnom Penh, Cambodia, it takes a true hero to take the leap. Scott Neeson, ex President of 20th Century Fox International and Sony Pictures, moved to Phnom Penh in 2004 and founded the CCF (Cambodian Children’s Fund). Fourteen years later, Scott Neeson has saved the lives of thousands of children; his charity has been awarded numerous times for its outstanding achievements and gained international recognition. A highly inspiring talk with a man who decided more than a decade ago to make the world a better place and never looked back.

By Victoria Adelaide | JAN 22. 2018

Victoria Adelaide: Mr Neeson, can you tell us a bit about your background?

Scott Neeson: I grew up in a working class area where there were no jobs and there was very high youth unemployment. People back then being on welfare was an accepted part of living there. The only major employer was General Motors. I dropped out of school in Grade 11, I never had my high school certificate. I applied to work at General Motors on the factory line but I got rejected because I didn’t have a high school certificate. So the government put me in a category called ‘Chronic Unemployed’ – high unemployment area, no job experience, no high school certificate – and under that program any employer that would take you on would get half of the salary paid by the government, so I could at least get work experience. The very first day I was sent to an interview with a group that had drive-in movies, drive-in movie theatres, as well as rural areas where they had cinemas and drive-ins. I was going to be the assistant there as well as one of the projectionists. I got the job and I worked up from there to President of 20th Century Fox International. For me, that’s more of a compelling and unlikely story than giving it away for a garbage dump in Phnom Penh. Giving it away was a very conscious decision, but moving from being an unemployed projectionist to running the studio, I think it’s a good story, but it’s not nearly as media worthy. While at 20th Century Fox, we pulled together, distributed and marketed some great films, Titanic, Braveheart, Star Wars, Independence Day as well as some really good small films, independent films that I was very happy to do. I was running the marketing for international, then I was made President, which is not nearly as much fun. It took me away from the creative people, the creative process, working with filmmakers, and all of a sudden I was in meetings on finance, profitability, human resources and then you are on bottom line stress. I just stopped enjoying it. I didn’t renew my contract. I signed a contract to join Sony Pictures, it was a very attractive salary and I took 5 weeks off to travel to South East Asia to see the Buddhist monuments starting from Thailand.

VA: Besides visiting the Buddhist temples what was your real motivation to visit Asia?

SN: I grew up in Australia, and my first overseas trip was to Bali in the late 70s, when Bali was beautiful, with few tourists, and all the areas were linked by rice paddies; there weren’t even roads, it was magical. I love the energy of Asia, the Buddhist culture or animism in some cases, the people. That’s why I took my vacation traveling through Asia. Europe is very established, I spent a lot of time working there, I don’t like visiting museums or seeing historic sites very much but the energy of Asia really attracted me. So I wanted to spend some time there and see Angkor Wat, some of the Buddhist monuments in Thailand and then travel to India to the very north, to Rishikesh which is the birth place of yoga and do some yoga for a couple of weeks. That was the plan. I came to Phnom Penh simply to get a flight to Siem Reap and I spent two days there to meet with a friend’s friend. Then I ended up spending more time there, initially just trying to do something with street kids. I thought I could help, but I couldn’t, because I was getting ripped-off, and it took me a long time to realize that the money wasn’t going anywhere; it was going to the parents or it was going to runners. First of all, I thought I was smart enough, as I was the first person to try to help these kids, trying to put in place plans that the kids would benefit from and not the parents. But I was so naïve; these parents were way smarter than me. I took two kids, some siblings, to a private school, paid for the enrolment thinking that way the parents wouldn’t be able to monetize it, but they did. They had a deal with the school, they got half of it back and the school got the other half. And one of them, a girl who was very appealing and very charismatic, had been registered eight times at that school that year and the parents had made several hundred dollars just by getting 50% of the fees. That was an eye opener. So the obvious question was, is there any place where there’s real poverty? I mean genuine poverty, no plan B and no one there trying to help, and that’s when they took me to the garbage dump. Goodness, that was the most appalling thing I’d ever come across. I’ve seen garbage throughout the country, I’ve seen poverty but something there was just shocking. It was the lawlessness, the break down of families, the idea that a mother would leave her children there when she got a new husband, things like that…and that rattled me.

Photo: Courtesy of Scott Neeson-CCF.

VA: It’s interesting that you’re saying that because during one my first trips to Phnom Penh, 10 years ago around the same period when you were there, I was also very shocked by the same things, more than what I saw in India…

SN: Yes, likewise. India is almost a part of a spiritual journey: the level of poverty, the caste system, there is a long history there, whereas Cambodia is broken; it really struck me as being broken. There was a war that killed 20% of the population, devastated the infrastructures, devastated the genetics and everything; that’s what really shocked me.

VA: Then something occurred that would change the course of your life, right?

SN: Yes, I hadn’t started at Sony. I didn’t want to leave to go back to join Sony but I did because I worked 26 years in the business, I had no real education, no qualifications, 26 years to get up to the position I was in. I didn’t want a mid-life crisis, I wanted to make sure this was real and sustained. I had 26 years in the business and nothing in the world suggested that it was a good idea; everybody thought I should just let it go and maybe send money over there and that I was out of my mind. People in Hollywood perceive themselves as being the center of the universe and you’ve got hundreds of people below you who want your job. You’ve got hundreds who would tell you how lucky you are, that your job defines you, so there was a lot of pressure not to go. I finally ended up commuting for 12 months by spending one week in Cambodia and three weeks in Hollywood. I initially thought I could make it work by sending all my money in Cambodia, but that wasn’t the case. There were two problems, one was that too many things can go wrong here if you’re not on the ground, not necessary just pilfering or corruption, but also if you genuinely care about the kids, they can be overlooked, they could be taken away. Some kids died before I could get back here. The biggest part too is the emotional conflict that I experienced. I mean, I would come here and I was so taken by the poverty, the level of poverty, it was horrendous, and then I would go back to Hollywood, where people were getting angry about how hot their latte was at Starbucks, where people genuinely take offense at not getting the right table at the restaurant.

VA: …and they create a scandal…

SN: Yeaah… and all of a sudden, the emotional pull between the two worlds became more and more severe. I’d made a promise not to do anything rash for 12 months, so I decided I would wait 12 months before making a decision. And it was 12 months almost to the day when the incident happened. The major actor of the moment was in Tokyo doing publicity, he had a private jet. Then I came to Phnom Penh and went straight to the garbage dump. A grandmother took me to a place where kids had been left and they were dying of typhoid, all under the age of 10. I’m not a doctor and I didn’t know Cambodia so I freaked out. They were literally dying, no one knew who they were, no one had the resources to take them to the hospital, people were all too busy. And that’s when I got the phone call from the actor and his agent, having a meltdown about amenities on the private jet. Our offices had put the wrong amenities on there. The beautiful point was that at one moment during the call he said, “You know Scott my life wasn’t meant to be this difficult”. Those were his words. I’m not involved in any organized religion, but if you’re looking for a sign, I mean that was it. Still to this day I cannot think of two more blatant extremes of squalor and poverty, children dying and such indulgence, self-centeredness and complete lack of awareness. The good thing with the call was that I got rid of any kind of doubt, I felt validated, I got clarity. I knew I was doing the right thing and all the people, and they meant well, all my friends saying that I was crazy, I understood why they were saying it but it didn’t matter anymore, I knew I was doing the right thing. It was a beautiful moment for me, it was a defining moment. I went back and that’s when I started the lengthy task of getting out of my contract. I had only been there for one year, and they didn’t want me to leave, first because they thought I was going to another studio and no one believed I was going in a garbage dump in Phnom Penh, and the other reason was just deception. I’d only been there for a year and I wanted out, and they didn’t want that; it looked bad for the studio, so it took me several months to leave. But I finally got out of my contract in December 2003 or 2004 and I moved to Phnom Penh 3 days later. And I cheated too because I had made a 12 month promise not to do anything rash, but during those 12 months, I sold everything. I sold my house, my car, everything. So I was sitting in a shitty rental house waiting to either quit or get fired and move over there. I thought I could stay for the whole two years, but there was no way I could, I was so unhappy.

VA: You were unhappy because the moment you went to the garbage dump in Phnom Penh, something happened to you…

SN: It was what I was meant to do. You find your groove, you find what you’re meant to do, your dharma and everything become easier after that.

VA: I guess you cannot go back to a more material/shallow lifestyle….

SN: No, no you can’t. That lifestyle is a great example of shallowness. It’s not the truth but it’s still very intoxicating. I do miss some things though…

VA: What do you miss the most?

SN: I miss a lot of things. I went back to America last October and I stayed in a hotel down on Venice Beach which is a very trendy area. I was sitting on the hotel rooftop and I went for a bicycle ride along the Venice track, which is what I used to do every weekend. People there are relatively affluent, there’s no one who is begging, starving, there’s the police there, there’s security. So, sitting on the rooftop, drinking very nice scotch, I was thinking that I really gave up an awful lot, and for the first time I realized how much I gave up. Sundays I used to play paddle tennis with some really good friends and I had a big motor yacht that I used to take out afterwards. That’s a really nice thing to do on Sundays, and I miss that. I miss my house, my dogs, I had a beautiful house, it felt like a home. You know I have those pains for all the things I miss, but the bigger point is regrets. Oh my goodness, I have no regrets at all about what I did. In the society we live in, it’s natural to miss things like that. People like to position you as being saint-like but you know, the truth is that I would rather spend Sunday on my boat than in a garbage dump. I’d rather spend my Sunday afternoon with friends on a very good salary than going knee-deep through garbage.

Photos: 1: Norman Neeson 2/3: Scott Rotzoll Photography 4/5/7: Courtesy of Scott Neeson-CCF 6: Samnang Chieb

VA: Yes but you are not the same person anymore…

SN: You know, I’m far from perfect. People tend to simplify things. Now I would much rather be here with the kids, with the families and the grandmothers than anywhere in Los Angeles. I hated going to the Academy Awards because it’s boring, I hated the meetings. I’m so happy down there, I have no regrets. If I hadn’t done this I’d have regretted it for the rest of my life. I’ve always had an innate fear, it’s an unusually strong fear of being 80, when I’ll be in my last years, and having so many regrets about the things I didn’t do. I don’t know why. What if I hadn’t gone to Cambodia? What if I hadn’t done this? It really scares me. I’m pretty sure now I would feel like I haven’t done enough with my life.

VA: When you arrived here, the idea was to help 80-100 kids?

SN: Yes, we had 45 and wanted to get to 80.

VA: Yes but now have more than 2000! (laughs)

SN: Ahaha…

VA: I’m sure in the beginning you didn’t envision that…

SN: No, that’s also something that people get wrong. People like to say that my vision has created this amazing organization. There was no vision, I was on the garbage dump and I was filled with anxiety because children there were in a horrible shape. The kids very very rarely ask for money, some would ask, ‘please take me to study’, and you had a child who has been abused, who has been abandoned in the garbage dump and I don’t know how to say no to that. So I brought them in and the next kids came along and it went from 80 to 200 to 500, 600, thousands, simply because they should be with us. It was just this inability to say no to kids who would come up to me. Even today, 4, 5 years old, they want to come and study. Here, it’s not something that is considered as a basic human right, for a kid to go to school, and it fascinated me; it shocked me that kids that young would seek education as a way out. So no, there were no great plans, I’m not a visionary but I am good at solving problems, so when we brought the kids in, it was apparent that without that income the family would be more hungry, and the other siblings had less food, there was no one to look after them. You brought another sibling and the parents had almost no income. That was when we started to add programs, rice programs, where all families with the kids in CCF get subsidized rice. If your child’s got perfect attendance, you get your rice for free, you have priority medical access, we pay all your medical costs regardless, but that does not include some serious illnesses, life time illnesses, diabetes. And that’s a big deal, because most people at the landfill are there because of illness; they got themselves into debt. And then every time you peel back the onion you find that for every issue there is a solution, and I enjoy finding those solutions; for me it’s part of my strength as opposed to having this big vision. So we started to build a hierarchy: if you were getting your children to school and you were not allowing abuse at home, physical, substance, or sexual abuse, then you would get good benefits. We would not let any family become worse off because a child was studying, and that became a very expensive promise when children were in a NCC of 10 -12 years in university. And of these first two hundred kids, 70% are in university right now, which is phenomenal. At the Neeson-Cripps Academy, 78% of the students are girls who are getting the same education, in engineering, technology. The academy is mind-blowing. We’ve got kids who study robotics, coding, 3D printing, green screen animation, special effects, chemistry labs, IT, physics, maths, photography, music etc… that’s every evening. What these kids are accomplishing is amazing considering the area where they come from, a very toxic area where there’s a lot of violence, and these little kids who were between 0 through 15 were wandering around, they had nothing to do, it’s dangerous. We just started a junior science club for the little ones; they can just see over the benches but they learn about magnets, basic chemistry. It’s fascinating to see all these kids in their little lab coats and they are just 14 years old, kids that have been with us for a while, it’s a beautiful thing. I don’t think anyone will dispute the fact that it’s the best education facility in Cambodia. The joy is that the poorest kids in Cambodia are now going there, and I think that’s an achievement. So this program will just evolve; we get a challenge, a problem, an issue and then find a solution. And most solutions are pretty straightforward, you’re not burdened by all the red tape of Western government and all those things. A good example is when we lost a couple of young children in accidents because the mothers go into the city to pick garbage, they pull the carts behind them. There are children in the carts because the mother doesn’t have any safe place to leave them and occasionally they get hit by cars. It occurred to me that on the 3 roads out of the garbage dump where the mothers always went, we had schools, so we set aside an area where the mothers drop them off. We’d have either a mother who’s been trained or a nurse looking after the kids. She would feed them and the kids would sleep there and when the mother would come back, she would pick them up again, and there’s never been a death since. That is great and it costs around $30 a month. The reason why these things happen is because I’m on the ground every day and every night. If I had stayed in Los Angeles or Sydney, I could have gotten a lot more funding but I would never have identified problems, I would never have been able to put together this model.

VA: Yes because you really need to understand how they live…

SN: Yes you have to. And I’m glad I didn’t have a non-profit background, because I went in there with a completely open mind. I accepted that I didn’t know anything, and then all these solutions came up. I was there for a birth and no one had a medical background; one of the women who helped with the birth messed up and the mother died, then within 24 hours, the baby subsequently died. That was when we started maternal care programs. And now we’ve been running the maternal care program for 7 years, 1600 births, the maternal death rate here is 6-7% every year, and we have never lost a mother. I don’t think anyone else has been able to do that. The thing that I find both good and frustrating is that the solution isn’t to put together some large aid organization for maternal care, it’s to empower the community. Grandmothers with some training can give advice to the mothers. We carry out blood tests for blood borne diseases, they’ve got water, a community youth check up, otherwise the community looks after them, and the cost is tiny because we have very low impact. We did 2 prenatal and 2 postnatal training courses, and all the large government aid agencies wanted to understand why we were at zero percent death rate and they were studying increasing maternal death rate. But you know they are geared toward taking an effective idea and selling it to the whole country. The way we have organise things in the community, you can’t sell that; you need to go into a community and replicate it, bring together the locals, train them, empower them, and then leave them alone. But they can’t get their minds around this because they don’t have a structure where there is an executive vice president of prenatal care or an executive director of postnatal care. The future of foreign aid is in replicating aid at a community level, it’s not in dropping money from above through bureaucracy. If we fall over tomorrow, the training we’ve done, the understanding, the responsibility remains; if these large aid organizations fall over, everything falls over, because they’re giving to people as opposed to training them. We need to replicate our model at a community level whereby people remain accountable, responsible and trained, and that’s the only way we are going to get significant change. I get the scaling up thing if you’re looking at a disease like malaria, smallpox; it’s much better to work on the national or international level. Issues like maternal care, domestic violence, women’s rights, you have got to do it in the community. So we are now at the stage of having the model of all these programs documented as well as the parallel funding model that goes with it, and I’m hoping it will be replicated in other areas. It’s essentially a franchise. I want someone in another country to look at it, understand why we get the outcome we do, and replicate it. You know here are just a few examples: when I arrived, the absentee rate at school was 52% because not many children were going to school; they had to work one day in order to go the next day. It’s now1/3rd of the US rate, and in Australia we’re at 3.7%; the level of retention went from 60% to 96%. Pass rates are just through the roof and all we did was take away the barriers stopping a child from studying. If the obstacle was the need for money, an abusive father, drug addiction or whatever issue with the parents, we just had to get through to them all, as respectfully and firmly as possible, as we needed to get the kids into school. And provided the kids come to school, then the parents are not worse off. We are very careful about ensuring dignity and respect of the parents. There’s a second tier of benefits which allow the parents to escape some of the debt. For the majority of families from the countryside, when someone got sick within the family, they sold off their possessions and they also borrowed money to pay for the treatment and medicine. The level of medical care outside of the city is awful, and the interest rate for the poor is between 10 and 20% a month. So if you borrow $300 for medical treatment, it doesn’t seems like much, but you pay $1.5 a day every day in interest alone; you never get detached to principal and these $1.5 a day keep accruing for the rest of your life. I know a lot of people who had a 50 dollar loan on for 10 years. So what we do, for the families that are getting the kids to school or at least are making an effort, we go to the creditor, we pay off the debt, whatever they borrowed, and the families can pay us back at regular interest rate. So repayments would go from $45 a month down to $12 a month and there’s an end date, and a year before the loan is over, we sit down with the parents and ask them if they want to start a small business once the loan is paid off, or if they want to buy back the family land. And what happens in those cases is that the father starts to come around, and this is a great thing. There is a high level of drunkenness, domestic violence, and the father is often unemployed. It’s my belief that because of such a patriarchal society in Cambodia, if the father gets in a position were he can no longer provide for his family and protect his family, the only way he thinks he can exert the patriarchal power is through violence. It’s his right to beat his kids and his right to beat his wife and that’s how he makes up for his lack with regard to other patriarchal duties. I find that when the father gets respect, when he gets hope and when he can provide for his family, things really calm down, gambling stops, alcoholism drops.

So the improvement is in the programs and the very top of our pyramid is housing. We have built 460 homes, the communities are amazing. All these homes have running water, bathrooms, a small garden, a temple. There’s a grandmother who is there for the wisdom, the values as well as acting as the ‘eyes and ears’, they’re always telling us if there’s any violence, or drug use, so we can know about it. And that is a great incentive when you concentrate on the good families that have that level of responsibility; it’s really effective, you can see it, people in many cases will improve their life in order to get one of those homes. My hope is that they stay there for a year or two until they get back on their feet financially, to help them clear their debts until the kids get into university. And it’s working, 70% of these kids go to university and they never ever set foot in a classroom. Education is great, going to university is an amazing accomplishment, however, if we are going to change the whole country, the 2000 kids who would go through the program need to have public communication skills, they need to understand social media, they need to have a thorough understanding of women’s rights, children’s rights, they need to know what to expect from the government, and to be able to do a PowerPoint presentation. Then 2000 can influence 200000 and those who want to get into politics can potentially influence the entire country. The leadership program is a 3 year program, it’s very well structured; Tony Robbins funds it and gives us 10 scholarships every year. So the top students fly to San Diego and have an intensive 3 day program at ‘The Global Youth Leadership Summit’, they come back here and they replicate it to all the kids who didn’t go. Now with a university degree, a knowledge of human rights, a knowledge of communication, that’s when you start to make an impact. So you start to get a well rounded citizen. Because of the Pol Pot days, the Khmer Rouge, parents today have serious post traumatic stress syndrome, they have very poor parenting skills, they can’t relate to their children. There are some silly things that people believe to be tradition, like not showing affection to the child, as soon as the child is old enough to walk and talk, at about 5 years old, then the parents, especially the father, will cut the relationship. And I was told that’s traditional, because they think that it’s not doing the child any favor if the child still relies on them. So at 5 years old, kids have to fend for themselves! It struck me that this is a survival mentality, it’s not cultural. So I started asking around to the grandmothers and they laughed, they said it wasn’t true, that they used to hug a child until he is 20 years old. So I went back to one of the guys I work with, the one who told me that, and I said to him, “You’re wrong; before the Khmer Rouge parents loved their children, they hugged their children”, and he said to me, “You know my grandparents told me that and I thought it was so weird and embarrassing; I never told anyone”. I said, “You better stop telling people all those things because your kids need hugs and need someone to listen to”. Then he said, “Look at this father, the kids are standing there asking questions, and their father won’t even look them in the eyes”. It’s wrong, we have to get over that. So it was important to instill wisdom, values, traditions, family structure, and that’s why the grandmothers programs are there, that’s why we expose all of our young teams to the grandmothers. They are amazing vessels of wisdom. I don’t really want to spend too much time on the Khmer Rouge because it’s so well documented, but I want the kids to understand that it wasn’t always this way, that domestic violence is not normal, that parents should be loving and hugging their kids, that schools were not always free, they were compulsory. They need to understand all of that. I want them to understand this beautiful tradition they used to have, beautiful traditions and games. The parents do not have the knowledge to pass it on and lots of kids are moving straight from a blank slate into Facebook and forgetting all about their culture. They have to understand their culture, understand how the family structure used to be, that mothers used to be the most respected member of the family and they have now dropped to the lowest level. So we try as much as we can to bring that around.

Photo: Norman Neeson.

VA: Are you planning to stay in Cambodia?

SN: I’ve got family here now. I’m torn, I don’t really have much desire to grow old in Phnom Penh, I don’t like it here that much. But I’ve got kids, they rely on me, so I don’t see myself moving anytime soon. Among the 2000 kids, there are about fifty to a hundred that I’m really close to, that I’ve been raising like my own, they freak out when I go away. I don’t know how they would be if I weren’t there. I don’t know how I would be if I weren’t with them. It was my dream to move on to the next place and replicate what we do with CCF. I was thinking of doing it in Nepal at the Indian border where there is terrible trafficking and abuse, and in Bangladesh by the Myanmar border, before the masses of refugees arrived, and then in Palestine. But I got really serious emotional ties here and I’m also way too tired to do it all over again. It nearly killed me so many times, it literally was exhausting living on that garbage dump every single day!

VA: Do you still do that?

SN: I go every night. The garbage dump is no longer there but the squalor around it hasn’t change one bit. I just don’t think I’ve got the energy to do it all over again and another point is that I can’t leave my children. People get really upset when I call them my children, but they are my children. I’ve been raising them, the parents abandoned them and they actually left for good. You know, there’s one kid that I’m very close to, the mother is a little crazy, she had a new husband and as is often the case, the husband didn’t want anyone else’s kids, and instead of bringing them to us, she tried to kill her daughter twice. She first tried to drown her and the second time she took a knife. Someone intervened, she was 3 years old at the time, she is now 12. I had the mother brought here with the kid, I asked her why she was doing that, why she didn’t bring her to us. She was angry and said in front of the kid that she didn’t want her and that if I cared so much I could have her. I remember telling her that I would be the luckiest man in the world if this could happen. And the kid is still with us, her mother kept having babies, she’s been in and out of detox, this kid is like my own. Now she’s turned 12, she’s got a lot of confidence and that’s a good thing. I adore her. And there are maybe another 30 or 40 kids who have similar stories.

VA: What is the achievement you are the most proud of?

SN: My proudest achievement is seeing the change in individuals. I’m proud of each individual, I take pride from these hundreds of kids, whether it was a baby that was abandoned and who would have died because he had congenital illnesses, or kids who go from being sexually abused to becoming community leaders. I see the kid in his individuality, it’s one at a time. People don’t understand and think I’m like ‘Rain Man’ because I know every child’s name and there are 2000. I know their names, their siblings’ names, I don’t forget names, how could I.

VA: Besides the need of money what are your main difficulties?

SN: One is to ensure that CCF can survive without me. And it’s not just about the money, it’s also having someone who could understudy, who could take care of outward-facing communications, donor sponsorship, marketing, grant submission. I need a person like that because, one, if anything happens I don’t want it to fall apart, and two, I don’t want to always have to work this hard. I want to spend time with my top donors, with the kids, with the families and with the grandmothers. I need that, I’m burning out.

VA: You said, ‘The poverty and suffering of others is our responsibility’ – do you think too many people do not feel that responsibility?

SN: Yes, I think social media’s done a lot to desensitize people, it’s full of a lot cynicism, I was very guilty of the same cynicism, I was not giving to charity because of the 3 basic prejudices people have:

– We don’t know where the money is going, fat salaries and everything else.

– It’s not my problem, it’s on the other side of the world, I’m paying my taxes, why doesn’t the government take care of it?

– I’m just one person, if I give everything, poverty and suffering will still remain.

But at that moment, the first time I was on this garbage dump, all those thoughts were gone, it was my responsibility, I didn’t know where my money was going but if I didn’t do something no one else was going to; children would perish or would spend the rest of their days there, in prostitution in the garbage dump. And all of these thoughts went out of the window. Unfortunately it took such a personal, direct, unlikely encounter to turn me around. But there’s got to be a way to connect people as closely as possible to the solution and for us to get out of the way, it’s the only way people feel a degree of ownership and then responsibility. A child sponsorship program, we can promote that, it’s a very good program.

VA: Do you think Cambodia gave you the opportunity to become the best version of yourself?

SN: Oh yes, yes, it did. I’m very happy with my personal evolution. I really do feel that I purged myself of the material goods, because growing very poor and all of a sudden having unlimited, semi-unlimited wealth, it’s intoxicating. But it’s not real; the things you own end up owning you. You have a great boat but you spend all your time paying, and mooring a break down. There’s a much better way, real lasting contentment comes from what I’m doing. Happiness is a subjective thing.

... The future of foreign aid is in replicating aid at a community level, it’s not by dropping money from above through bureaucracy``.