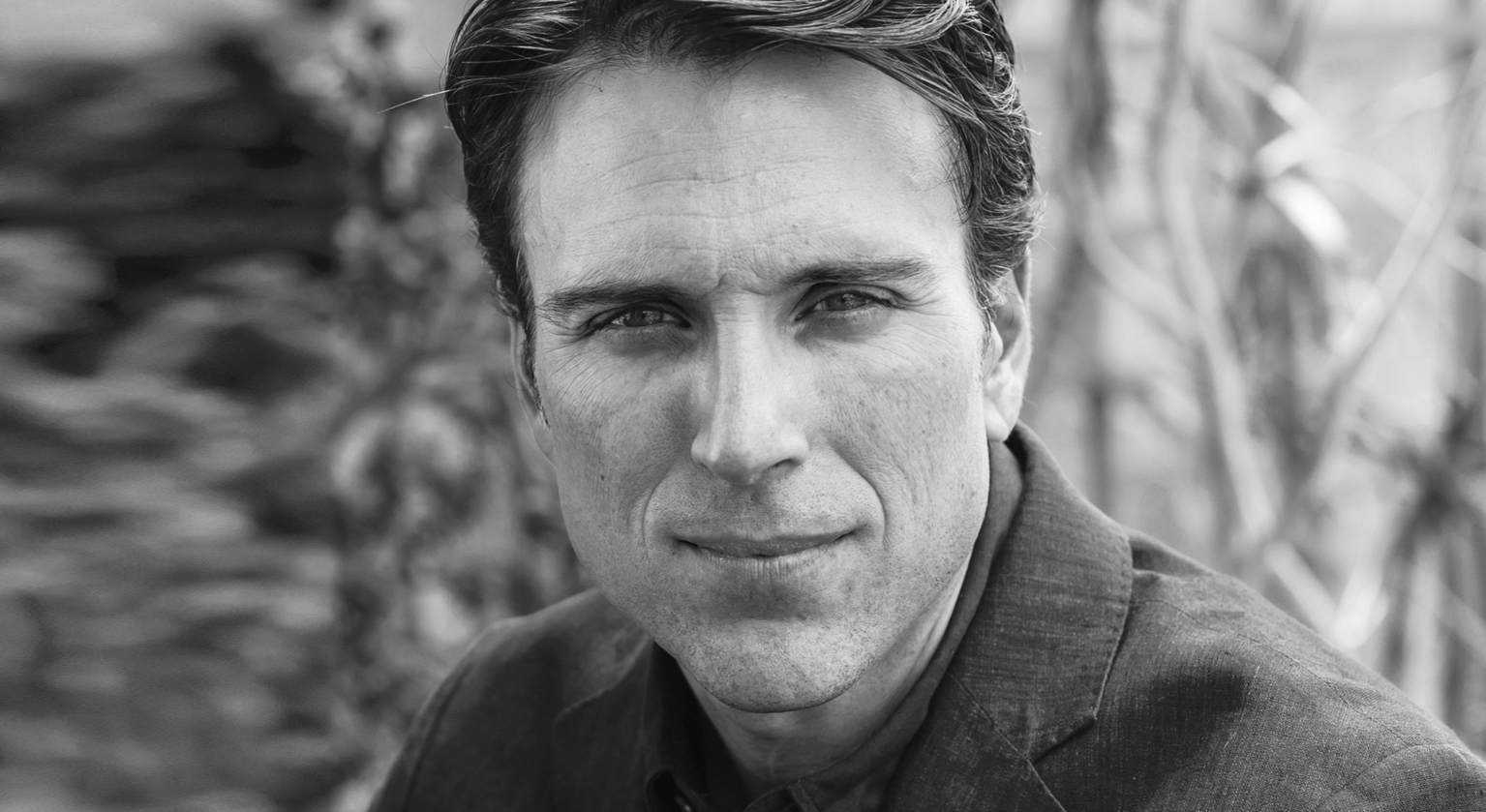

04 Jun Jonathan Baker

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Baker

Jonathan Baker

Producer, actor, director, teacher, and musician, Jonathan Baker is a man of many talents and many interests. Executive producer of the Sundance Film Festival’s recent Audience Choice Award Winner Crown Heights—a biographical film portraying the true story of Colin Warner, who was wrongfully convicted of murder—Baker is a well-rounded individual who seems to transform everything he touches into gold. Founder of JB Studio, JB Productions, and New Renaissance Entertainment, his latest production is the feature musical film Basmati Blues, starring Donald Sutherland, Tyne Daly, Brie Larson and Scott Bakula, released in theaters in February of 2018.

By Victoria Adelaide | June 04. 2018

Victoria Adelaide: You are the executive producer of the movie Crown Heights, the true story of Colin Warner. How did you get into that project in the first place?

Jonathan Baker: I received the script through a series of mutual friends I shared with the screenwriter. We were looking to make something special. On the cover, it said the story was based on This American Life, the famous radio program. I was maybe 20 pages in when I realized I had actually heard this story many years ago during the broadcast. I remember sitting in my car for an extra half hour listening to the show, absolutely riveted by the story. When I read the script, on page 62 when Colin marries Antoinette in the prison, I began to cry in the middle of this cafe. I immediately thought, “We’ve got to make this movie.” I texted my partner Nnamdi, who read the script and kept texting me, “Is this as good as I think it is?!” (laughs) and I said, “Yes, this is really good; this is an amazing script.” And that was it. We got together with Matt Ruskin, and that was the beginning of Crown Heights.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Baker.

VA: Several movies you have produced have a very powerful message…

JB: For me, it’s about breaking down boundaries and finding common ground—working through the challenges in our society in which good people come up against tough obstacles and make the best out of them. I try to find stories that are inspiring. There is always a hero and a journey, that’s it.

VA: In 2007, you left Sony Pictures Entertainment to found JB Studio and went on to develop and educate over 150 artists. How did you do that?

JB: They started coming to me. It was a really big change in my life. When you’re working at big studios like Sony Pictures, you’re working on anywhere from six to ten movies at the same time. However, as I say to my students, you really only like one of them, and the rest are maybe not your taste. It’s a big business; you’ve got to make money. It becomes relatively emotionally empty and you feel artistically hollow after so many years working on various projects like that. I was getting older and I thought to myself, “If you have to do this, you better do it soon. You don’t have kids, and you only get to take these giant risks when you’re young.” So, I jumped ship and left everything I had behind. I had been writing a lot of songs about my mother’s death. The only way I could survive the studio was to go home at night and write music on my piano. I was going through a lot; I’d lost my mother when I was 20 and was trying to find my way. I had taken all these corporate jobs to make a living, but I felt disconnected from my art. I finally decided to leave the studio to produce, direct, and star in this crazy musical movie about a guy who has a recurring nightmare that he wakes up in public naked. I put this short film into production in 2007. It was ironic, because within two weeks I was shooting it at Sony with a lot of Sony’s help. I invited several of my old musical theater friends from the University of Michigan and Broadway to help me. As I was finishing the film, it was as if everybody started coming to me and asking, “Can you help me with my idea?” or “Can you get me ready for this?” or “Can you teach me how to sing?” etc. So in 2007, I started with two clients who just kept calling all their friends, and the studio took off from there. Crown Heights came out of that studio. It was Nnamdi who came in through Kerry Washington, and Kerry Washington came in through a voice teacher that had done Moulin Rouge, and I didn’t even know that she knew about me! All of a sudden, I was working with celebrities. I didn’t know where they were coming from; it just happened.

VA: I heard several big movie producers say they do not make money with films anymore. You are doing extremely well with your business. What is your perspective as an independent producer and what change did you notice for independent producers from the moment you started to now?

JB: My perspective is rooted in my experience from the studio I worked at and my position now working on independent films. I’ve been going to the Sundance Film Festival for twenty years. I had my first short film there when I was twenty, and now we’ve won the audience choice award with Crown Heights. I’ve seen it all, up and down the ladder. After two decades watching this industry play out, it has started to strike me that the movie business is very much like any other market. There are waves; it goes up and down, it’s always changing. The biggest shift I’ve seen in my life is this macro shift between the international market and what’s called the domestic market, which is the United States and Canada combined. When I first started in the movie business, it was a 60/40 split where the domestic market owned a 60% market share and the international market had 40%. In the time that I’ve been working, those percentages have flipped. Now, the international market represents 60% and the domestic is only 40%. It’s a huge piece of the puzzle that we’re still negotiating with. That’s why you see a lot more films with stories that cross over—stories that deal with China and other territories. The big studio films have to tie them together, because they want the entire market from all over the world to find it interesting. What that has done in the short term for us, regarding independent films, is what some would call “the bottom falling out” of the film industry economically. We have also seen massive technical advancements, allowing what I call a “flood of content.” Everybody can make a movie with their iPhone, but that doesn’t mean they can make a good movie. There is an issue of craft now. Because there is a massive amount of content being created, supply and demand makes it competitive for buyers; the price point has been reduced; stars have become more valuable, and they only work within certain price ranges. Therefore, the budgets that range in the middle and bottom suffer. Ultimately, we can see that the industry is expanding. The question is now, where do you fit artistically? Do you want to make this movie, or do you want to make that movie? And are you prepared for the economic model that really represents right now? Does your idea economically work? The big challenge in film is that it takes a lot of money to get good at it. It’s very expensive to learn, like a surgeon who has to go through 10,000 hours of medical school. You have to go through years of training with someone who is better than you at a very specific craft. Many artists don’t realize they’re going to spend a lot of money simply learning. There are tons of risks and very little reward unless you stick to it. I often tell people that the only way to get successful in this business is to stay in it. Don’t go anywhere; do not give up! The system is evolving. Every time there is a market wave, it will correct itself. There’ll be some adjustments and there will be new technologies, such as virtual reality. It will always keep expanding, and I think that’s really exciting.

VA: You worked for major companies such as Sony Pictures Entertainment, Screen Gems, and TriStar Pictures. What did they teach you?

JB: Confidence. Working for the biggest companies allows you to gain confidence. You then have to jump into the biggest arena you can and see what you’re truly made of. There’s this warrior mentality that has to be a part of your soul. You have to believe in yourself enough to get in the game. Then, when you emerge from those environments, you’ve already been at the top with the biggest and the best. That confidence stays with you in any room you enter from that point forward, because most people haven’t had the experience. You have a certain level of knowledge and respect that allows you to continue to harness your greatest potential. I think that’s really the biggest part of it—to continue looking within. I was a very small piece, low level in many respects, of a very powerful, very successful company. It was extraordinarily valuable because I was learning from people that had way more experience, more insight, and the ability to teach me what I needed to learn. I went to New York for that reason; I went to LA for that reason; I wanted to get with the people who knew best.

VA: You seem to be equally comfortable both as an artist and as a businessman. How do you manage to have such great balance? Does it have to do with your upbringing?

JB: I am dyslexic, which was one of the primary reasons for my entry into music. My mother realized I was not learning. I couldn’t read, so she started me on instruments and said, “Well, while we tutor him, while we teach him to read, he needs to also do something he’s good at so he doesn’t lose his confidence.” I soon after began on the drums. I was teased as a child, I was ostracized. So, from age 6 to age 18, I worked my way up to academic success and simultaneously learned how to read. At the same time, I could drum, play other instruments, I had a really strong ear, and I was good at it. That was the balance that gave me the strength to overcome my disability. A lot of people ask me separately about the business side and the artistic side. To me though, they are complementary. I think we’re inherently very creative, and the brain is a problem-solving engine that applies itself in many different ways. Society may call you this or that, and try to pigeonhole or label you. Great artists are the people who are always reinventing themselves, who never let themselves become labeled as just one thing. They want to spread out, they want to take their talent and engage with it.

VA: How do you see yourself in five years?

JB: I’m very blessed because my partner and I are producing three Broadway-bound productions. We’ve moved into theatre, we have a few TV projects we’re developing, and we have a lot of great feature films on the horizon that are very exciting. We have a really nice flow. The heart of what we’re trying to do is make sure we’re being socially conscious, responsible artists. If we do a movie, the message is a helpful one. If we do a Broadway show, it’s a constructive show. Let’s be beneficial to humanity; not just hit a nerve and sell fear. We have a responsibility as artists to inspire the best side of humanity. We should be on each other’s team; we should be bringing people together. It’s the primary responsibility of the artist to experience the world in a certain emotional way and then translate it into products that people can learn from. I think edu-tainment is a big thing; to be able to service the viewers with catharsis and help them heal. I hope you see what we do in the next five years and find our message a helpful one.

VA: What are you working on now?

JB: The movie I’m working on now is called Private Sky. It’s a musical that is being produced as an animation and it contains only original music. In my early twenties, after my mother died, I moved to New York to try to find my way. I ended up on Wall Street and working on Broadway. I suffered a serious accident, went through medical bankruptcy, and experienced 9/11 all within a couple years. After 9/11 happened, I finally started writing music about my experiences. The result is Private Sky, and I’m extremely excited about bringing this film to life over the next couple years.

...We have a responsibility as artists to inspire the best side of humanity.``