08 Jun Dayle Haddon

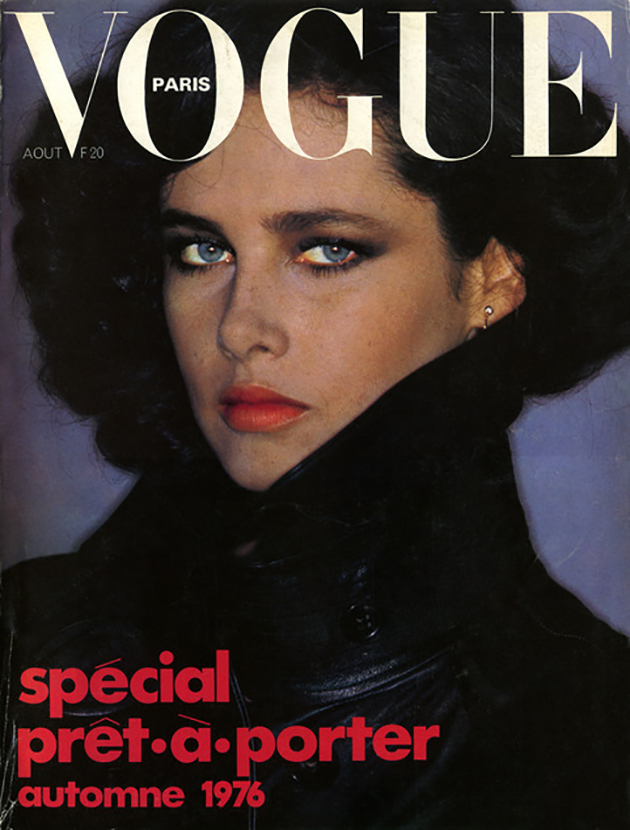

Mrs. Dayle Haddon is represented by Iconic Focus Models | Photo: Maher Attar | Instagram | www.maherattar.com

DAYLE HADDON

Where do we start when speaking of a woman who has spent her entire life empowering other women? Undoubtedly one of the most recognized faces in the beauty industry in the early ‘90s, Dayle Haddon shattered age taboos as the first supermodel representing women over 40 with her multiyear contracts with L’Oréal and Estée Lauder. Advocating in a space where no one had ever ventured, Haddon redefined the notion of aging and opened the gates of the beauty industry to women of all ages, shapes, and styles. A woman of many talents, Haddon enjoyed a successful career as an actress and is the bestselling author of two books: Ageless Beauty and The 5 Principles of Ageless Living. Raised by a family who always gave back, her second chapter in life as a humanitarian for various organizations is as remarkable as her first act as a legendary beauty pioneer. Haddon became a Goodwill Ambassador for UNICEF in 2008, and this role took her to faraway lands such as Sudan, Angola, Rwanda, Congo, and Kenya. Haddon is the founder and CEO of nonprofit organization WomenOne, which champions quality education for girls in Kenya. Dayle Haddon is still modeling and is currenlty represented by Iconic Focus Models.

By Victoria Adelaide | June 08. 2020

Victoria Adelaide: Following a stellar career as a model for some of the biggest brands, in 1986, at 38 years old, you became a single mother after your husband’s death. When you tried to go back to the beauty industry, all your attempts were dismissed. Can you tell us about that period and how you rose to the top again?

Dayle Haddon: I had lost my husband, and I had a young daughter to support. I was working as an actress at that time and everything was shut down to me. I reached out to the beauty and fashion industry to see if there was work there. To my big surprise, they responded, “You are over the hill; you will never work in this industry again!” I was only in my thirties, and a billion-dollar industry was telling me that I was finished. I knew they were wrong! I was just at the beginning of who I was, certainly not at the end! I went to the library, and did a lot of research. I found that there were more than 43 million baby-boomer women whom the industry was not addressing. All the creams, the magic potions, were being advertised on 20-year-old girls who certainly didn’t need them. Subconsciously, they were saying to women over 40, “You are of no value. You are invisible!” I decided I could change the perception of aging from the inside of the industry out. I was one of the first people on that wave in the early 90s. After they had told me that I was over the hill and would never work again, I signed a contract with Estée Lauder, followed by a 15-year contract with L’Oréal. I wrote two bestselling books, Ageless Beauty and The 5 Principles of Ageless Living, on the value and the wisdom of getting older and toured all over America, Europe, and China speaking to women about the power of aging. It was fascinating for me to share with women what I had learned and then listen to them and understand what they wanted. I wasn’t over the hill, but starting again in a different way!

VA: So you really made it!

DH: I made it, but it was hard, and it took time for it to take off, a bit like crawling up a glass wall. This was very new thinking at the time. Aging was not an inclusive idea, it was exclusive and dominated by youth. I was trying to get the message out that there was more to the understanding of beauty. For one to be an authentic beauty, it would have to come from the inside and include all ages, instead of their idea of just a wrinkle-free beauty. We, as women, had to look at the power and beauty which comes from within. With age, we gain wisdom, stability, and balance and there is great beauty in that. Having worked with so many gorgeous women in the modeling industry, I often say that physical beauty has a two-minute grace period, then you must deliver something more! I know it might sound cliché, but true beauty most definitely comes from within, especially as you age. At 20, you can get away with not delivering a whole lot, nobody is expecting that much from you, but by the time you reach 40 and above, you have to be offering a lot more than just what you look like!

Photos courtesy of Dayle Haddon.

VA: According to the New York Times, you have shattered age taboos with your multi-year contracts with L’Oréal and Estée Lauder (among other companies). At the time, you were the first supermodel representing women over 40. Today, age is no longer a barrier. How does it make you feel when you see so many models of all ages?

DH: I think it’s great because in the beauty industry we have to reflect the world we all live in. We have to be inclusive when we speak to women. When I first started as a model, there was only one style of beauty: the tall, Texan, or Swedish girl, with long blond, straight hair. That was the definition of beauty; even brunettes were not included. At that time, very few brunettes made the covers of magazines. Today, we are expanding the idea of beauty in terms of race, age, and size. Also, young people need to have older and different people imaged for them so they are not afraid to move forward on the time track and feel included. Many young women in their thirties or forties look at me and ask, “What do you do? How do you stay that way? What do you eat?” I think one of the keys of moving forward along the timeline is to know how to take care of your skin not only on the outside but on the inside as well. What are you thinking? What are you doing in life? How are you treating others? Your thoughts show up on your face, and your sense of value about yourself and others and your place in the world, is what makes you feel beautiful and therefore, look beautiful.

VA: In 2008, you became a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador. How did you transition from the beauty industry to being a humanitarian?

DH: I think it’s essential for women to reinvent themselves at times in their lives. You may be a career person and identify yourself as such, or you may define yourself as a mother or as a leader. When that role moves you into another phase, there is an opportunity to go back to what you may have put on the back burner because you were busy doing something else; raising a family or working on your career, and start something new. I’ve reinvented myself so many times because certain roadblocks came up. Some doors became closed to me and even though I did have a feeling of loss, I eventually realized those blocks were also redirecting me towards other opportunities. New doors opened once I understood that.

I was raised in a family that always gave back. I had been working with women—regular women—all over the country, in Europe, and in China with my books and lectures and felt that I wanted to work with women in more extreme situations, so I approached UNICEF. They had difficulties in getting their stories out and I had access to those magazines that could print them. So we started that way: I would go through the story, find the best one, and reach out to the magazine editor and say, “I think we should do a story about this.” Then, I realized I was one degree away from the actual story, telling the story but not actually traveling there myself, telling the story first hand. I went back to UNICEF, and said, “I think that we should work together,” and they agreed. My first trip was to Darfur, in Sudan where I spoke with women in refugee camps about their lives and their challenges. Then from there, I’ve been in maybe 11 or 12 countries, including Congo, Angola, Rwanda, and Kenya. I’ve held the hand of a young girl as she fought for her life, been held up by gunpoint, been lost on one of the most dangerous lakes, Lake Kivu and traveled through rebel territory in the back of an ambulance. I did a lot of different things, and I met and listened to many women and girls in many difficult situations.

VA: During your tenure as a UNICEF ambassador, you traveled all over Africa—to Darfur, Angola, Rwanda, Congo, Sudan, Kenya, and so on. Has your contact with these disaster zones changed you? How did you cope?

DH: There are different ways to cope. I have a philosophy that I am a spiritual being having a human experience, not a human being having a spiritual experience. So, when I go there, I go with that view, and I try to put myself in their place. My role with UNICEF was to bring attention to what was happening to these women so that they could receive aid and attention to their stories. On those arduous trips, you find out who you are and who other people are. Some people break down crying, while others are challenged with some of the experiences.

One of the trips to Rwanda was extremely hard. We were shooting a film, and I was in a church where 50,000 people had been killed by machetes. Their bones, their skulls, were there, and the families could only recognize them by putting their initials with a felt pen on the bones. Almost 20 years later, they were still finding the bones of those killed. Their clothes are placed in piles on the pews of the church and you can feel their presence. Because of the filming I had to stay in the church for a very long time. I could feel the horror that had taken place there. My system, my body, could not take it, and I started getting sick. They had to take me to the hospital. For me, it was unfathomable that one human could do that to another. Most of the work we do though is different. Often I end up sitting with a young girl, or a woman, holding their hand, listening to their story as they share their difficult journey and that exchange is so powerful, so human that I feel it is an honor to be there and its transformative for me. I return home with a better understanding of the world and have more compassion, more gratitude, patience, positivity, and more hope.

VA: Did you ever feel in danger going to those places?

DH: Darfur was level 4 security, level 5 being the ultimate. There is a whole protocol—you have to pass tests, you must know what to do in case of emergency, you have to go through training for your safety, so you come back exhausted. To travel there may take up to 24 or 28 hours. It’s rough, very hot, little food and difficult dusty roads. You’re going from refugee camp to refugee camp, clinic to clinic and you see and hear terrible things. So, it’s not for the faint of heart.

VA: I guess there is a time of reflection when you come back from these missions?

DH: My travels to these remote places make me more grateful for what I have on this end. I have less complaints about what I’m going through and more gratitude for what I do have. I am so inspired by their capacity for joy no matter what their situation! And that is something to think about! In some ways, both worlds offer something to each other and I often I am actually getting back more from them by their sharing their stories and their lives with me.

I’m fortunate to have been able to go there because I don’t have ties that hold me back—my child is grown, I have the freedom. However, not everybody has to go to Africa to help. You can help in your backyard, in your neighborhood. You can support people with organizations like myself or other organizations, and then we go to these places and bring back the story.

Photos courtesy of Dayle Haddon.

VA: In 2008, you created your non-profit, WomenOne, which is a charitable organization focused on the education of girls and women. What was the turning point that made you decide to create your charity? Can you tell us about the work you do within your foundation and what the current projects are?

DH: First, I’d like to say that anybody who wants to know my story can read my two books: Ageless Beauty and The 5 Principles of Ageless Living. What happened was: I went on a trip to rural Angola with one of the big organizations I was working with, and there was a clinic there. Women had walked all night with babies strapped to their back to get the medical attention they needed in the only clinic in the area. So, when we got there at 6:30 or 7 in the morning, the front of this rural clinic was dotted with women and babies. And inside, it was packed. We took a tour of the clinic, and one of the doctors pulled me aside and asked, “Could you help me?” I replied, “Sure, if I can.”

Then he said, “We cannot do our work properly—we are missing two microscopes. Could you help us?” And I said, “Yes, sure I could help you with that, it shouldn’t be a problem.” So, I went to the people I was traveling with and told them the clinic needed two microscopes. Then they looked at me and said, “Dayle, that is way too small for us.” I thought that it was not too small for those women who walked all night to be there. That’s the moment I got the idea to start my own non-profit. At first it was based on whatever was needed, then after a while I got more specific. Although clean water, vaccinations, all these things are really important, the key to everything is education—educating girls. Girls change the community; boys do not necessarily do that. So, I decided to work with girls and secondary education. That’s when you are most likely to loose a girl. Most girls at age 12 and 13 are either married off to a much older man or they are taken out of school and brought back to the family to work at home, or some are even sold. For every year we keep them at school, they have a better chance to be healthier, have a marriage that is not underage, have healthy children, and probably educated children. A lot of people ask why I focus on people so far away instead of helping people close to us? The world is getting smaller, and we need pockets of stability and calm all over the world. Women are the base of the communities. They found out in Africa that to break a community, you don’t have to go out and kill everybody in a village—all you have to do is break the women. If you do that, you break the stability of the community and everything falls apart. And in the reverse, it works with positive results—if you build up the women, you then build up the community. According to the UN, if you educate one girl, it’s like educating seven people. So, that’s how it started. Now it’s hard to raise money. With the current coronavirus crisis, I can’t travel, I can’t go there, so we are trying to find other ways to help them.

VA: So, how do you manage to help them?

DH: We’re trying with my board, together, to find new ways to help the girls. Our main work right now is in Kenya. Our girls there don’t even have water or soap to wash their hands. Most of them have single mothers who must go out every day, even though it’s not safe, to make money to support and feed them. They will sell vegetables, labor on a farm, or clean a house. Whatever they can get. If they can’t do that, they don’t have anything to eat. Many of them are subsiding on only one meal a day! So, we’re putting together an Emergency Coronavirus Relief Fund to get them through this time. Even though we impact more than 5000 children in the area, we have about 60 girls who have shown leadership qualities and we give them special life skills training and directly support them and their families. We don’t want them to fall behind in their learning so we are trying to switch them over to digital learning. The government sends them their courses to continue digitally, but our girls are so poor that they don’t have a computer or a phone to work on. Part of our Emergency Covid Relief Fund we have launched is to be able to purchase very inexpensive phones or tablets for them to receive their courses and for them not to slip through the cracks. Otherwise, we’re going to lose them and a whole generation of leaders that could help move the country forward.

VA: Throughout your travels, you have interviewed countless women in extreme situations, bringing their stories to the world. How do you allow for Western audiences to understand life stories they have never experienced and which may seem quite foreign to them?

DH: I think that people, generally speaking, are very compassionate. They do have a natural inclination to help. If I can make the stories personal, if I can meet the girls myself, hold their hands, listen to them and then come back and tell their stories, people can feel it in a more personal way and then have the desire to do something about it. If they know that they can get a report on their donation and what happened to their money, and have a personal connection to the girl they are helping, then it’s easier for people to understand and then to support our work.

VA: Among all these stories, is there one in particular that you could share with us?

DH: We have one girl—she was 14 when I sat with her, held her hand while she told her story. Her name is Rachel. She is a Maasai. At 14, her family wanted to marry her to an 80-year-old man. She wanted to continue her education. They insisted, so she ran away from home, put herself in the tree in the wild thinking, “I would rather be eaten by wild animals than marry an old man!” She spent the night in the dense woods and when the sun came up the next day, she thought, “I lived through this, now what am I going to do?” She got down and she made her way to us because the people know about our center there. It’s in a small town in Kenya, in the north of Nairobi. She came to our school, and she is now excelling in her studies. When we find these girls, we first contact their families, to get their agreement for them to be at our center. If they don’t have the money, and most of them don’t, we support them through their education and the teaching of life skills at our Center of Worth. Some of the children start out in the street at eight years old selling themselves for a piece of bread or a bed to sleep in. We can’t force them to come, but we offer them an alternative by getting an education. We feed them, make sure they’re healthy and in contact with their family. Most of our girls come from the street, and their families are so poor they cannot look after them.

Research has proven that when a girl is educated violence goes down, the occurrence of HIV/AIDS is less prevalent. Her ability to earn money and help her community goes up with every year she stays in school. If a woman can read, there is a 50% chance for her child to live beyond the age of five. So it’s just horrible when we lose girls. Every year, we have to go to convince a family by explaining to them that instead of keeping a girl back at her home to work, we think we can help them more if they keep the girl at school. We do home visits regularly to make sure the family is ok and bring some food and necessities, and that helps the family as well.

VA: How much is a donation to help a family in those troubled times?

DH: To support a girl and her family of five or six people, with food, soap, and water during this time for one month, it is $77. This does not include the phones we need so they can receive their school lessons we will film for them buy them for. We are trying to put the life skills lessons we are teaching our leadership cohort at our Center of Worth on film making them digital so the girls can keep up their studies. All those essential needs during this crisis would be about together $100 to $120 per family.

...My travels to these remote places make me more grateful for what I have on this end.``