05 Feb Alain Ngann

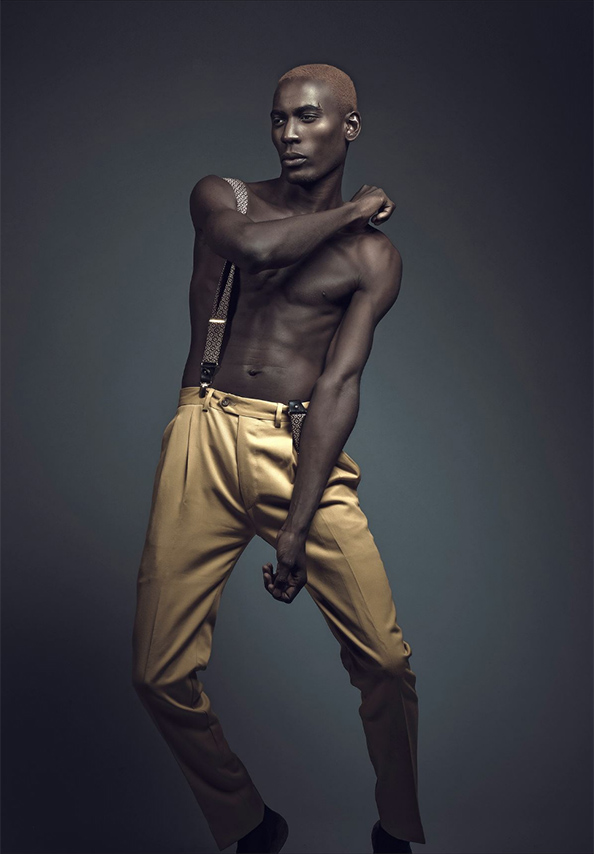

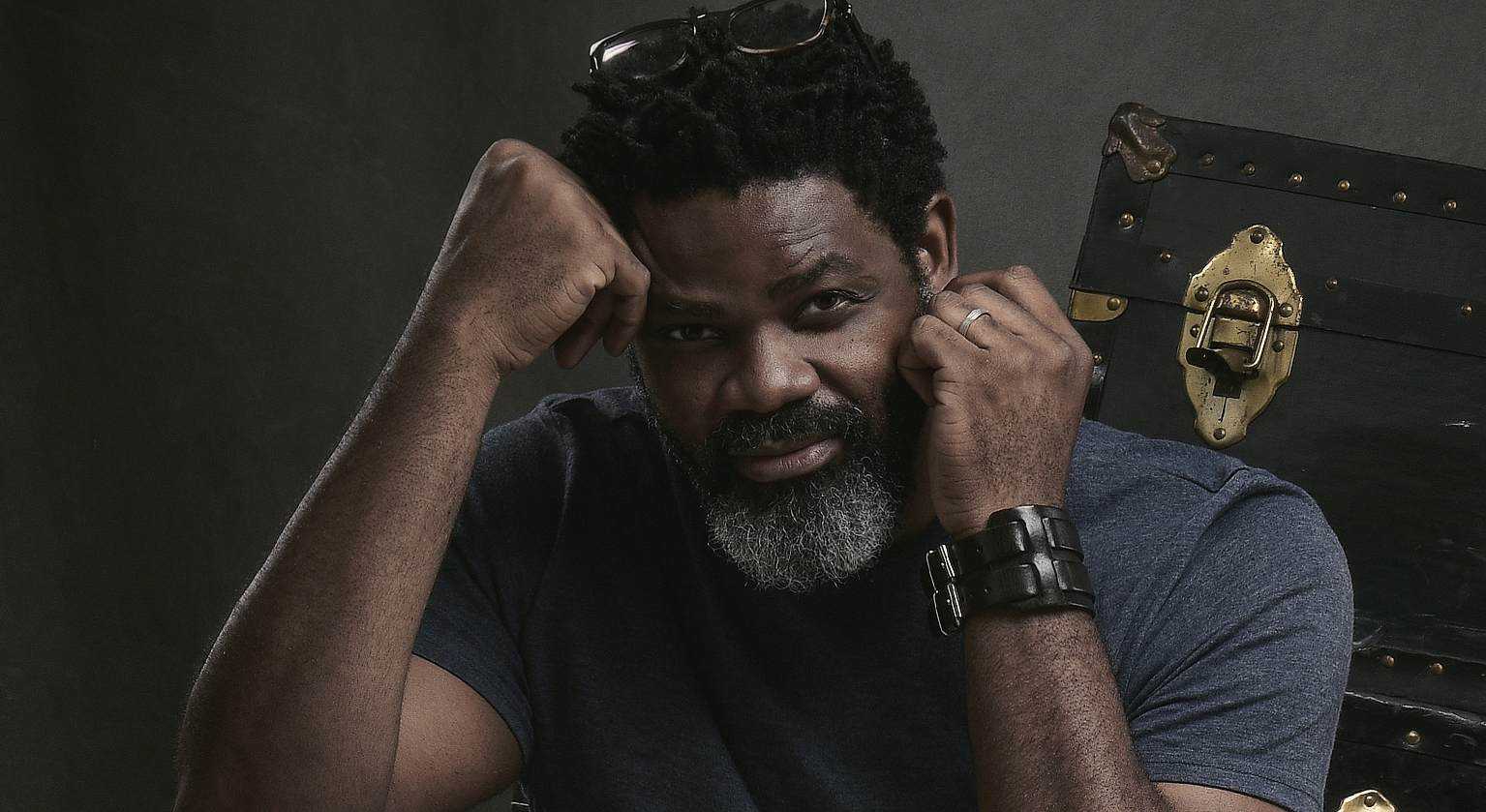

Self Portrait: Alain Ngann.

Alain Ngann

Cameroonian photographer Alain Ngann has been acclaimed by his peers for the quality of his work and for his creativity, recognized far beyond the borders of Cameroon. The initiator of a campaign whose aim is to raise awareness and change the public opinion on albinism, Alain Ngann is undoubtedly the rising photographer to watch.

By Victoria Adelaide | Feb 05. 2018

Victoria Adelaide: Mr Ngann, can you tell us a bit about your background?

Alain Ngann: As a youngster, I had a talent for drawing and I loved it. My father was an engineer who graduated from ‘Ponts et Chaussées’, so building was really his thing and he really inspired me. It’s very naturally that I turned into a creative career. So when I decided to study architecture, my father was really concerned and wondered if it was a good idea given the atmosphere in Cameroon. He asked me to give it a second thought and to be sure whether I wanted to do it as a profession or as a hobby. But I was stubborn, that’s what I wanted to do, so I studied architecture for 3 years in Paris and when I came back to Cameroon I began to do internships in architecture practices. From that point, I started to be interested in design, graphics, and I started to create logos, and things like that. At the time I started a communications company and I was working with other photographers, enjoying a great reputation as a creative, but my interest in photography came much later. In architecture, we do black and white photography; it’s about building, it’s very structured. And I think I kept this kind of architect’s mindset in the way I like to do things, in a very structured way, it has anchored in me. Black and white photography had a big impact on my first two years in architecture and then a few years later, around 2007, I realized that we always had to fly in foreign photographers from abroad, or as a creative, I found myself having to go online to download or scan pictures, so at some point I really found that ridiculous. We had what we needed here, why not try to do it here, ourselves and locally? So I tried, some people gave me their trust and it all worked out. I kept going; I kept learning by myself, I’m an autodidact. And then I had the opportunity to take a photography course that really helped me a lot. I’ve been lucky to have a teacher who taught me how to use light instead of teaching me photography itself, the creation of a lighting plan with 8 different sources of light, creating emotion using light.

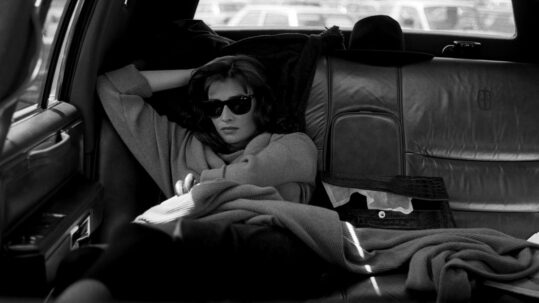

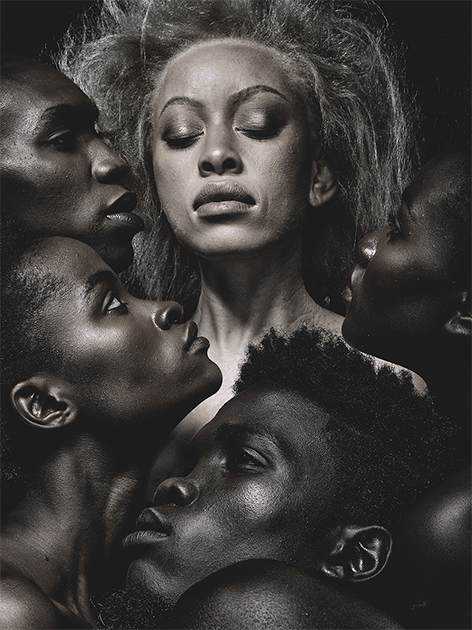

Photo: Alain Ngann.

VA: Who has been your biggest influence?

AN: I am really inspired by Annie Leibovitz; I also love the work of Terry Richardson but the one who truly had the biggest impact on me was French photographer Guy Bourdin.

VA: You do a lot of fashion photography but at the same time you also do a lot of socially engaged photography. How do you position yourself?

AN: Well, initially I started by taking photographs for advertising. And nowadays it’s advertising that feeds photographers. Fashion can give you visibility but it doesn’t really pay, here at least; you don’t have fashion designers who can pay you a fortune for a photoshoot. When it comes to causes, there are so many out there. I think I have always been greatly influenced by foreign advertising pictures on causes such as HIV, diseases, car accidents, because they often carry a very strong and powerful message. I was impressed by a photographer like Oliviero Toscani, who did the Benetton campaigns. He always had very strong images, using very few words but both combined together were always very powerful. It’s something that led me to do more and more refined work because when you are a graphic designer, a creative, you are always building, cutting etc… so it changed the perspective I had on my work. As for everyday life, when you move around the country you see extraordinary things but you don’t really have the opportunity to capture anything because people here don’t let themselves be photographed. And when you see all of that, of course at some point you’d like to do something.

VA: You are well known for your exhibition showing the beauty of albinos. What prompted this initiative?

AN: Well, actually two albinos came to see me, a man and a woman, not to take pictures but to work on a campaign to raise awareness about albinism in schools; they were looking for sponsorship etc..so what I offered them was to do a photoshoot, then to involve personalities and in the end I managed to have the photographs displayed in Douala. So it was very interesting. What moved me the most is that in fact we see them every day, we know them. I wasn’t aware that some of them faced challenges until I found myself spending hours talking to them and hearing them telling their stories to one another but with a lot of detachment, with the benefit of hindsight, and sometimes they even made fun of themselves, they laughed. And that’s when you realize that there’s not a day that goes by without them being exposed to taunting, insults. And you look at these people who are just like you and me but who suffer twice as much as everyone. People insult them on a daily basis.

VA: You tried to contact other albinos but the outcome was not what you expected…

AN: To do this campaign, we needed more people. So the two albinos who came to see me first, put me in touch with other albinos who are in the same organization as them. When I contacted them, some of them were very sceptical, others just didn’t care or asked if it was paid. The feedback was very negative. In the end, from all the people I called, and I called many, only 5 or 6 took part in the campaign.

VA: How did you manage to make them feel comfortable in front of the camera?

AN: It came a little bit naturally but the first thing was to create this connection. I think we made each other feel comfortable. We went to the studio, we spent hours talking, laughing and they had incredible stories to tell. One of them who is an artist, told us that his friends call him the ‘Finnish Guy’. And we jokingly kept calling him that. Surprisingly they are not sensitive at all in the end and that is amazing. So we really had some good laughs about it and I think it made them feel comfortable. Then when we started to do the first photo test, they loved the pictures, and they were like, ‘wow it’s beautiful’. Then we started taking photos of black people, mixing them together, playing with contrasts and we found ourselves very quickly in a very cheerful atmosphere where everyone was laughing, very participative and happy to be around. And all the people I invited to come and take pictures with them actually came. We took the pictures and the albinos ended up being shot with personalities, because all those people are well known faces, TV presenters, people like that. We really had a great time.

Photos: Alain Ngann.

VA: What feedback did you get?

AN: It was a disaster. Frankly I was very surprised and very shocked at the same time. The people I received the feedback from have shown a high level of ignorance; they asked questions like, ‘well what is that, is it a condition ?’. They had no clue. And it was the subject of very aggressive discussions on social networks, with people saying that we didn’t take pictures of real albinos, real albinos have spots, they are like this and like that etc. … it was crazy. In the end other people intervened, got into the conversation and started explaining that it was a condition. So well, the discussions went very far, it was really bad but I think many people learned a lot and that’s what matter.

VA: So you think in the end you reached your goal and ignited a reflection in people’s minds?

AN: Absolutely. I really didn’t expect that. I thought we were going to do a campaign with beautiful pictures, but I did not think it would be so educational. And it really was.

VA: Isn’t this project also in some ways what makes you stand out from the crowd?

AN: Absolutely, because it’s very hard in photography to be able to tackle topics that make you stand out. And I think in this campaign there is a fashion approach to something social.

VA: How would you define yourself?

AN: How would I define myself? Well, I’m not going to say as an activist, but I’m socially engaged and my positioning on certain things is clear. As an artist I generally express all of that through my work.

VA: You have expressed concern about the fact that step by step the young generation is losing its culture and mimicking the West.

AN: I think our biggest weakness is the fact that we are losing our culture, our roots. We are completely colonized in our head and we find ourselves at a crossroads. On one hand we are Africans, Cameroonians, but at the same time if we don’t have this Western culture we can’t sort things out. It’s almost as if we have to be able to mimic what’s going in the West. But is that really who we are? I’m not so sure. And it’s complex especially when on the other hand there are people who look down on you. I lived 10 years in France and sometimes I found myself in situations where I would sit in the subway, and the girl next to me would get up and leave, or a granny would be clinging to her bag. And yet I lived in the 16th arrondissement of Paris, but I still experienced that. And when you return to Cameroon, you have regrets. I don’t even speak my mother tongue, not well enough and I wonder why I was not taught to speak it. I mean, I am the youngest in my family; I have big sisters and I remember the time when they would go and spend their 2 months of summer vacation in our village. They spent summers in the village. And I would go and spend 2 months in France. Now, when my mother speaks to me in Bassa, I listen, I can understand certain things but when I try to speak it’s a disaster and that’s a shame. In connection to that I think we have to return to our roots to be stronger. Because if we lose our roots we are nothing.

Photos: Alain Ngann.

VA: Do you plan to export your work internationally?

AN: Absolutely. For me that would be the greatest reward. Sometimes I hear people say, “oh this guy is the best photographer in Cameroon or this guy is the best photographer in France” etc. …, we cannot say things like that, it doesn’t mean anything. There is no photography ‘in Cameroon’, there is no photography ‘in France’, there is only photography and it must be done properly. To export your work you need to touch a different crowd, have your work recognized by another audience and that’s important. That would be great.

VA: Have you got a favorite picture?

AN: No. I feel like I haven’t taken my favorite picture yet. I’m still looking for it.

VA: What is your relationship with your work and what message would you like to spread?

AN: There are many young photographers who do a lot of things but I think they’re a little too fast. The other day one of them asked me, ‘how can we become a photographer like you?’. Well, I had a father who set very high standards. He truly had an impressive culture; he was the kind of person who would tell you ‘go and read’ when you said something stupid; he hated mediocrity. Obviously having a father like that had its impact on me and the message I would like to give to those guys, and it’s a message that can apply in many areas, is that we have to set high standards both for ourselves and in our work. Don’t settle for mediocrity, reach for the moon. Don’t post a picture just to post a picture, don’t give it to your client if you’re not convinced by what you did. Today those guys don’t put themselves under pressure but they still get work because people are always looking for the cheapest.

...I think we have to go back to our roots to be stronger``.