21 May Nomin Bold

Photo by Baatarzorig

Nomin Bold

Nomin Bold is a rising artist in Mongolia. Trained in the traditional Mongol Zurag painting style, Nomin has become well known for her work mixing Buddhist imagery, which she uses as motifs and symbols of past traditions, and modernism. Through her paintings, Nomin raises awareness on the cultural identity crisis and hopes to ignite a reflection on the importance of keeping tradition alive in the modern world.

By Victoria Adelaide | May 21. 2018

Victoria Adelaide: Why did you start painting?

Nomin Bold: I’ve loved drawing since my childhood, so my parents encouraged me to become a painter. This is what I love to do and I’ve never looked back.

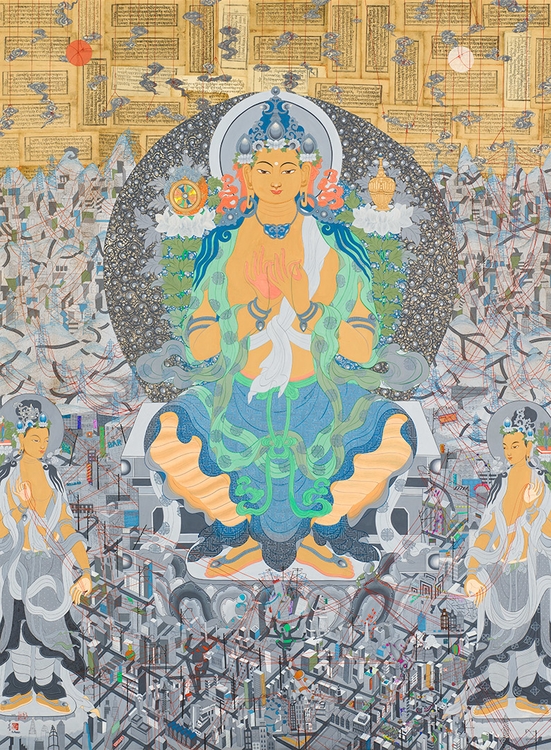

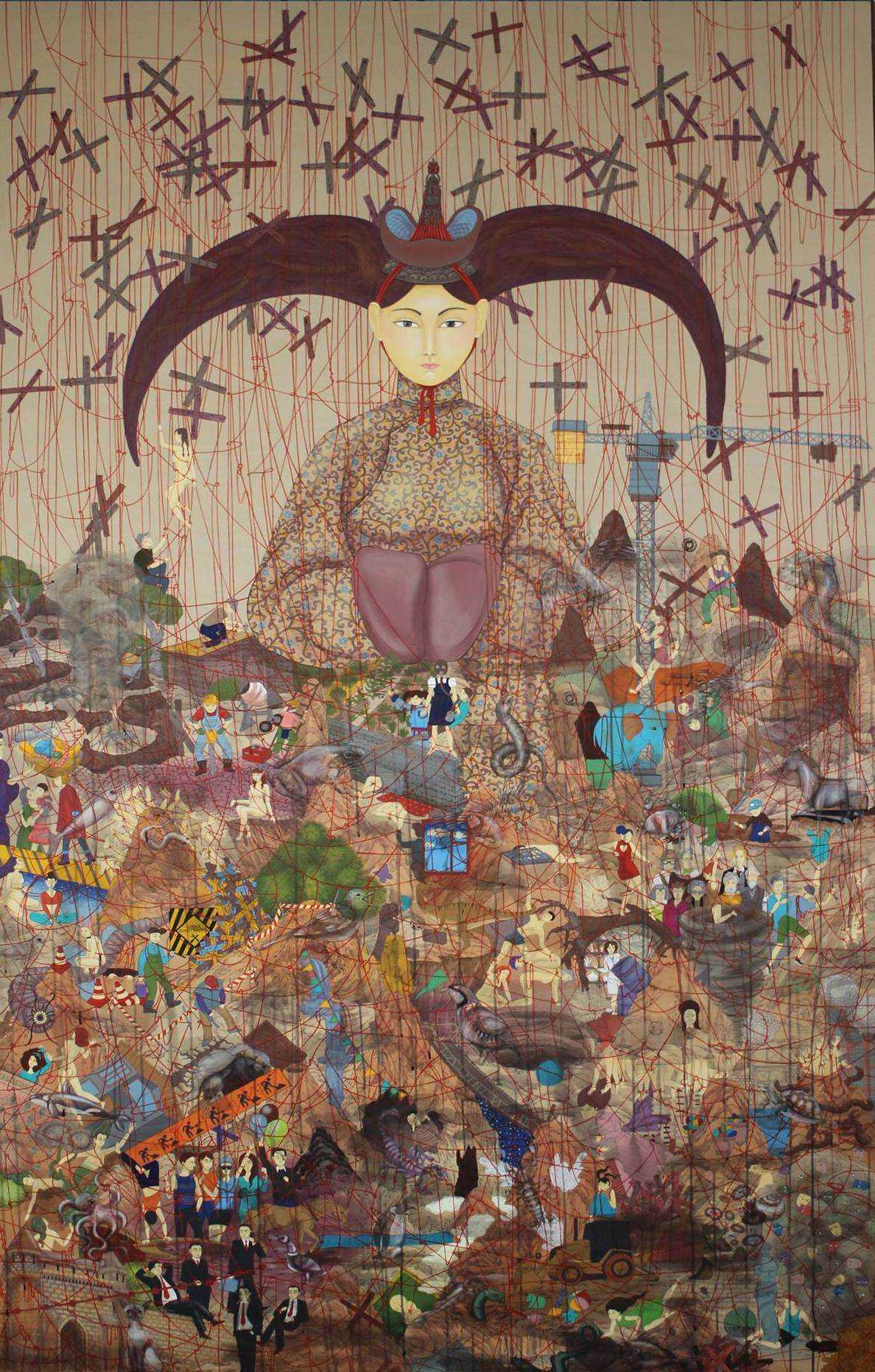

“EARTH” (soil) 2019 – acrylic, canvas (245x145cm) | Painting by Nomin Bold.

VA: You belong to the new generation of Mongol Zurag artists. Can you explain what this means?

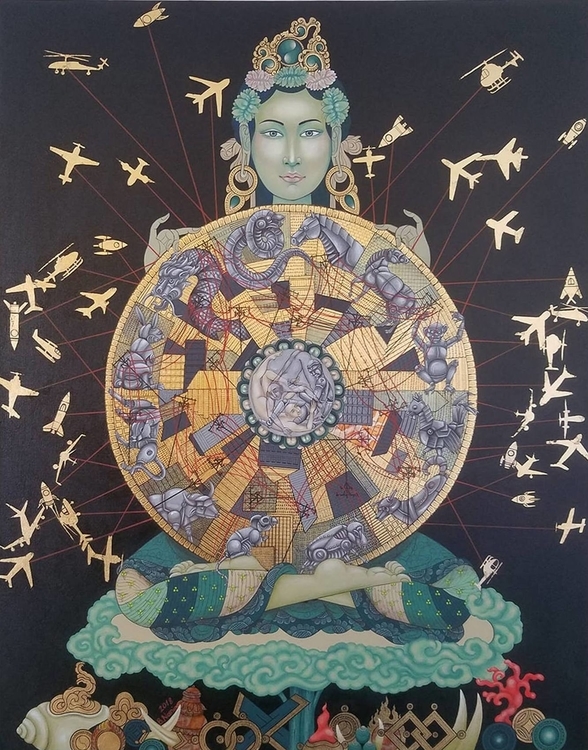

NB: The Mongol Zurag style was pioneered in the aftermath of the 1921 Revolution when the social situation changed in Mongolia. Consequently, it was impossible to recover the Buddhist thangka drawing techniques and to reconsider and show interest in past history as well. Thus, artists were challenged to experiment in a restricted extent by themselves. They practiced Western drawing techniques, then created many pieces of line drawings and became the main artists of their time. However, those works were disregarded because they were judged as childish, poor, lacking in perspective, and shameful compared to Western paintings. Today, it is recognized more explicitly that there is a strong truth, which is briefly stated in the Mongolian drawing style declaration: “Nomads represent the truth that will remain in the heart, instead of the truth observed by [the] eyes.” This is where the spirit of Mongolian drawing style lies. Perhaps because art was perceived from different perspectives, the essence of Mongolian-style drawings was identified only when modernism was introduced to European art. The singularity that makes Mongolian-style drawings so spectacular is their ability to make everything possible by representing any time and space on one canvas.

VA: Ulaanbaatar, the city in which you live, has changed a lot over the past few years. How do you feel about all those changes?

NB: Change and evolution are always welcome. But when it’s happening too drastically, as it is in this case, it makes life chaotic, uncomfortable, and this is not something I enjoy very much, I have to say…

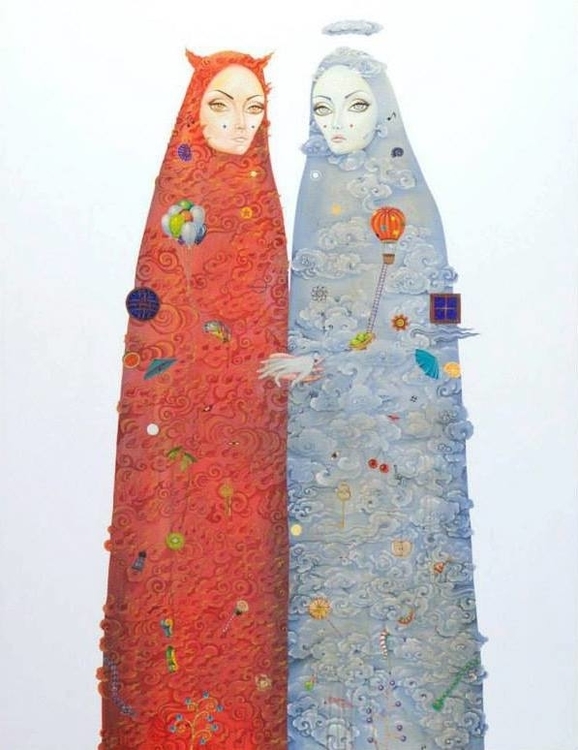

VA: Female figures have an important place in your art. Why?

NB: Female figures play an important role in what I do because I do not know men better than women. (laughs) Some say that in Mongolia, women and men have equal status. However, I think the different genders cannot have equal status. A man can never be like a woman and a woman can never be like a man. Genders have been assigned to humans for a specific purpose, following the natural order.

VA: Combining tradition and modernism seems to be your trademark…

NB: I picture it through my work because globalization is an inevitable aspect of human society. We may not like it—we may protest, object—but, in the end, it’s impossible to stop it. It is definitely the responsibility of every nation to preserve its traditions and heritage.

VA: What would you like viewers to reflect on when viewing some of your work?

NB: My goal, and what I’d like to point out to people, is that they must respect the earth and Mother Nature. I really would love for people to become more conscious about the need to take care of nature and our planet. It is never too late to do the right thing; we can start now.

Photos courtesy of Nomin Bold.

VA: Do you think art will always be used as a source of reflection?

NB: Not everyone is gifted with artistic abilities or a creative mind. So, when we are, our art must be original to first catch people’s attention then, later on, people will start becoming interested in its meaning.

VA: What is your creative process and how long does it take you to finalize a piece?

NB: It depends. The longest piece I’ve ever had to do took more than a year to be completed. But, it was not an everyday effort. I was working on it occasionally when I had the time. It’s important to keep in mind that every piece of art has its own processing rhythm. It’s on a pulse and creates itself at its own pace.

VA: What are you working on right now?

NB: At the moment, I’m working on a piece called Love.

VA: What would you do if you were not an artist?

NB: I’ve asked myself that question a few times and I’ve never found the answer. So, I suppose I must be involved in something that is so extraordinary, so precious to me, so great, that it makes it impossible for me to envision myself doing something different.

...every piece of art has its own processing rhythm. It's on a pulse and creates itself at its own pace.``