18 May Martel Chapman

Photo courtesy of Martel Chapman

Martel Chapman

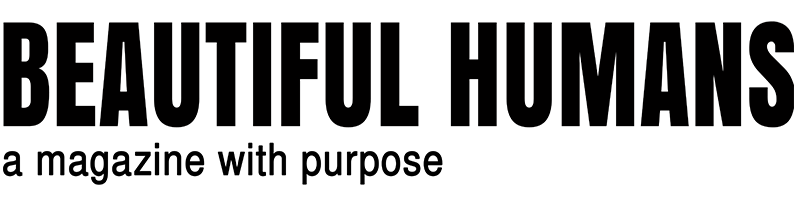

Martel Chapman is a painting genius who transforms sound into forms. A jazz music lover and educator, Chapman gives a brand new life to jazz and to the musicians who create and play that music. Through his art, Chapman invites us to an anthology of visual sonorities showcasing jazz giants in the noblest uncharted way.

By Victoria Adelaide | May 17. 2021

Victoria Adelaide: How did you come to jazz?

Martel Chapman: It was through John Coltrane’s Blue Train that was reissued in 97. Music was always a part of my life growing up. The radio was always on in the house. My parents listened to oldies, and I got my taste in music, rock n’ roll, heavy metal, and hip hop. As I grew older, I started looking for music that I could explore and live with for a while, and jazz ended up being that. I wanted to learn more about the musicians behind the music. These musicians were described as artists, and it was the first time that I came to know of musical artists being deemed artists. So that was interesting as it gave me an indirect way to explore visual art through sound art. I try to investigate what sound can do to influence forms and incorporate that. That’s always been the force behind everything I’m doing—the wonderment about everything; I have always actively pursued this by just wondering about it.

VA: Sound to forms—How does it translate in terms of colors and shapes?

MC: Jazz music, to me, did more visually than anything ever has. When you take a jazz standard that has been recorded or first composed hundreds of years ago and then performed in countless different ways, you can tell what song it is. Still, there are variances from time to time, even from a recording studio to another recording studio, especially in live recordings. The best example is John Coltrane’s My Favorite Things. He recorded that for 13 minutes in 1961. He continued to explore the idea of that melody throughout the rest of his career, even to the point where he recorded it five years later in Japan for over 50 minutes. That in itself is enough for me to wonder, “well, if we can take a sound and transform it that way, we can transform forms as well.” If I were to take, let say, classical music, I’d paint something photo-realistic; it’d be based on the composer as depicted in reality. If we talk about a pop tune or a comedy, we might do a caricature of the composer or paint something comedic, characterized, or poppy with bright colors. If we are going to paint jazz, in my perspective, we can paint it any way we want, but to me, an improvised portrait then. When I’m taking with jazz music, the idea is to incorporate forms and shapes created as a portrait. So, taking inanimate objects and turning them into an animate object or forms wouldn’t make any sense because we’re just building it. We take notes out of the air and try to put them together. Hip hop, for instance, would be like a collage, because with hip hop, they use samples, and change them up. Romare Bearden’s work, for instance, is visual hip hop. Considering these factors, it can be said that jazz allows for that freedom of expression, as it is in music as much as it should be visually.

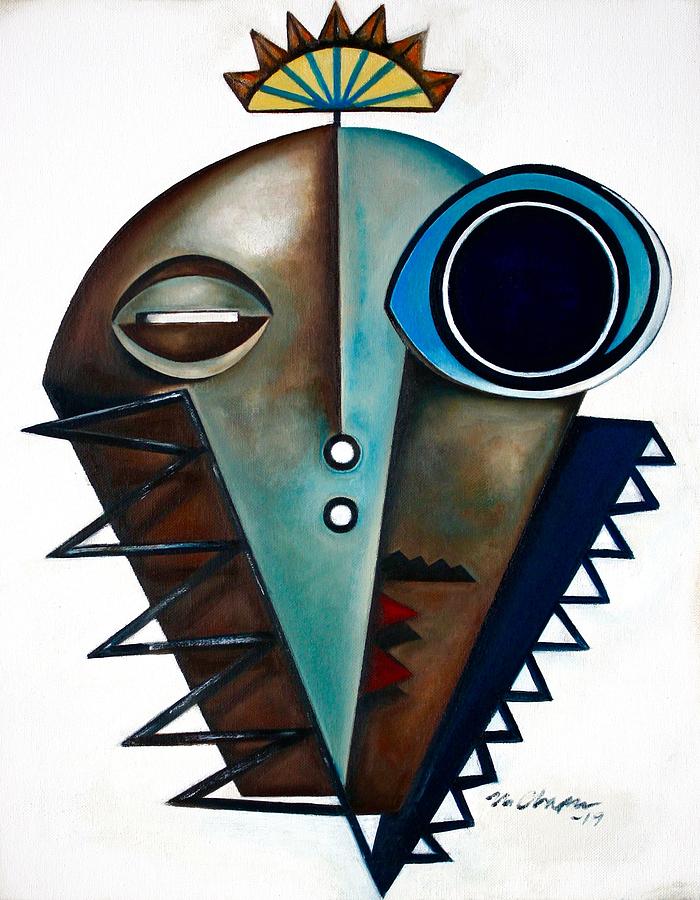

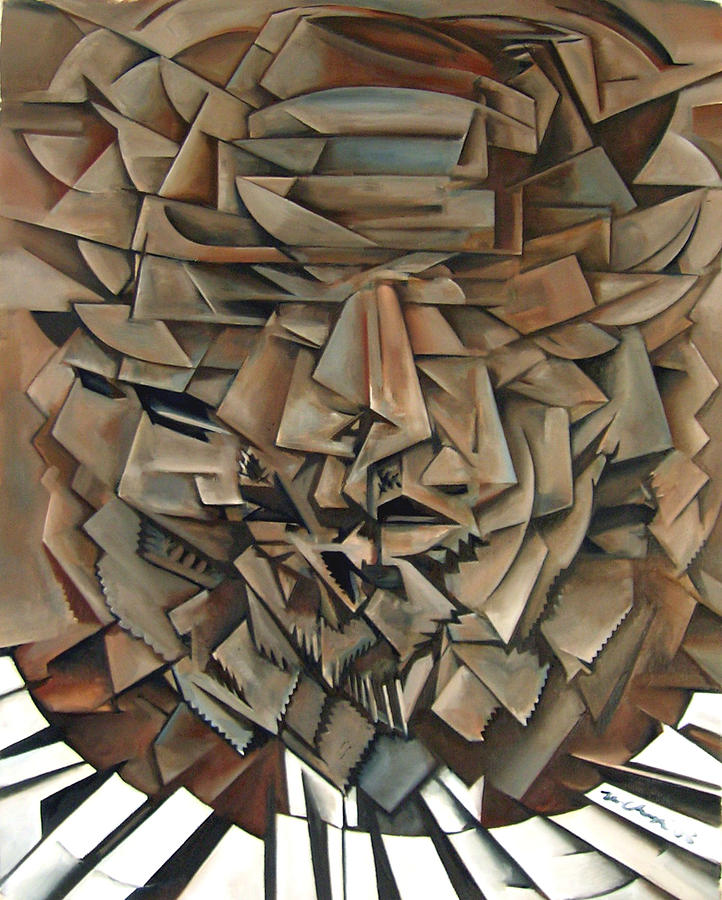

Paintings by Martel Chapman.

VA: Would you describe yourself as a visual interpreter?

MC: I like interpreting and incorporating musicians with their compositions. One of my favorite songs by Thelonious Monk is Blue Monk, so I painted him in blue. It depicts the Blue Monk—Thelonious Monk in blue. Something else that inspires me is the wonderment of what another song would look like. For instance, for Epistrophy, another one of Monk’s compositions, I painted him as the tune. The definition of an Epistrophy spells differently from composed; it’s just a repeated phrase in a circular form as in prose. You have all these elements from different disciplines coming into play, and I try to investigate and interpret all those to combine into one, to give a mystic lens of what it might be. I abstractly painted Monk as if he’s facing you with the keyboard in front of him, wearing his hat. His beard and face abstractly rotates in a circular pattern, in a repeated form as the term Epistrophy states.

VA: Jazz indeed opens up many doors.

MC: Yes, jazz does open the mind up to different ways to understand what we’re listening to. When jazz musicians play, they’re telling us their story, and it’s not a closed story; we’re open to the experience. Jazz music opened it completely for me. When they start their solo, it is almost like the stage disappears. It’s just them in a vast landscape. That’s perhaps what it does to our perception while we listen to it. That’s the amount of interaction I gain when I’m listening to the music, and my art is dedicated to it. I wasn’t taking art very seriously until I got into jazz music. It definitely changed my life. It opened a pathway for me to walk on, to observe, listen, and learn from. If I learned anything from jazz musicians, it’s the ability to interpret things after the experience. It is because of the musicians I listen to every day that I came to know certain ways, and do the work I do, which is painting jazz-related portraits. And it all comes back to that sharing aspect, giving back something that I’ve learned from that.

Paintings by Martel Chapman.

VA: I can see the influence of African art in your paintings.

MC: African culture and art is very inspiring to me, and it’s another way of sharing that influence and shedding light on it. Like jazz music, it wasn’t a real popular art form when I started shedding light on it. Maybe some people I knew didn’t know enough about jazz music, so they got to know me, and they got to know a bit of jazz music [smiles]. I like to expand what I’m learning and spread that out into other people’s life as well.

VA: How does feedback affect your creativity?

MC: When I’m here in my room, painting, it’s just me, the painting, and the music. While I’m working, that’s where I want to be. If I want to take a break and see how it is received, that’s another part of it, but then I just get back to the easel; that’s the whole idea.

...When I’m taking with jazz music, the idea is to incorporate forms and shapes created as a portrait.``