04 Nov Marie-Thérèse Mendene

Photo: Free of rights

Marie-Thérèse Mendene

This is our second interview with Marie-Thérèse Mendene, Cameroonian activist, psychologist, and founding director of M.O.M Sunshine—a center dedicated to assisting workers with chronic diseases and HIV. Marie-Thérèse Mendene has been fighting an uphill battle for decades to enable people who are HIV positive to access treatment. In this interview, Mendene shares her observations of the disease, her daily battles, and her brightest hope for those who are HIV positive.

By Victoria Adelaide | November 04. 2019

Victoria Adelaide: In 2001, you created MOM sunshine. Has access to treatment been made easier since you started?

Marie-Thérèse Mendene: Yes. In 2001, the cost of medical treatment was 200,000 CFA francs per month and now it is free. There has been a tremendous evolution—that’s unquestionable.

VA: What are the main challenges you face now?

MTM: The biggest challenge we face now is access to treatment for opportunistic infections and chronic infections that are linked to HIV, such as tuberculosis or hepatitis. The main issue is the purchasing power of the population and the people who are confronted by this problem. When they have an opportunistic infection, they fail to have all the required medical checks in order to take care of themselves. There are chronic and opportunistic infections that need to be treated before starting the HIV antiretroviral treatment and some people cannot access the antiretroviral treatment until they have been treated for their opportunistic or chronic infections.

VA: Why is that?

MTM: This is because there is no social security to cover diseases. People are unable to support themselves because there is no social security and they have nothing to eat. There are two problems: the purchasing power and social security.

VA: You said the other challenge you face is when the drugs are out of stock in the country?

MTM: Yes. The other challenge we face is that there are constantly breaks in the treatment. HIV treatment is a lifelong treatment to be taken every single day. It should never be stopped. However, when the drugs are out of stock on a national level—meaning they are unavailable in the entire country—no one cares anymore about the person. So, on one hand, we put pressure on the person for them to take their treatment properly and, on the other hand, they are left on their own when the drug is out of stock in Cameroon.

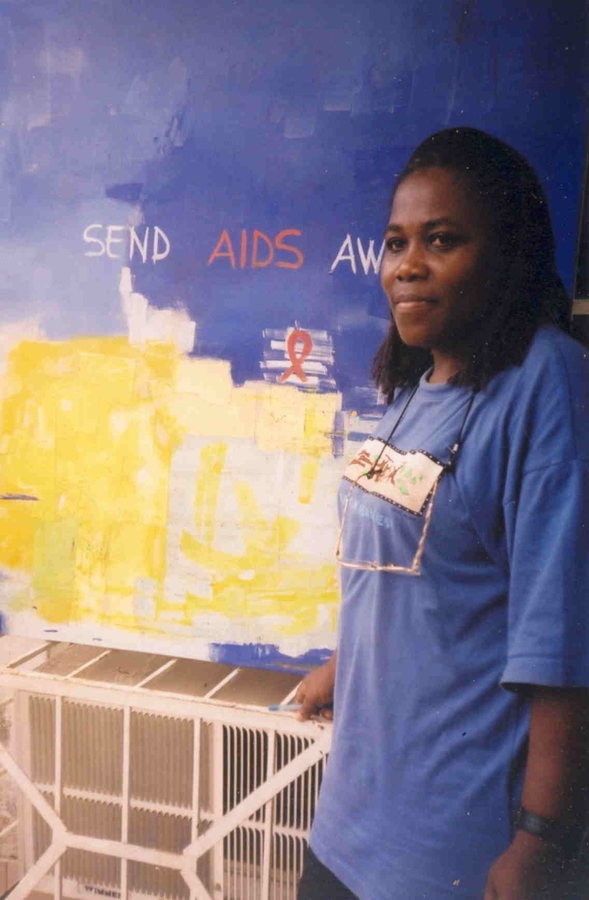

Photos courtesy of Marie-Thérèse Mendene.

VA: How do you deal with companies and what kind of work do you do within the company itself to change attitudes towards HIV?

MTM: We introduced a program about 16 years ago. First, we started raising awareness within companies by organizing conferences to raise people’s awareness of all the problems of discrimination against those affected by HIV, to let them know the company or the state can make medical treatment available to them. So now, companies are implementing programs that are supported by public officials and by United Nations’ agencies. Nearly all companies are aware of this and organize campaigns to educate and raise awareness within their structure. So, things have improved since we started. The discrimination that used to take place in 2000 has also taken a different turn because our role as an NGO is to defend and support workers who have been discriminated against. This means that when a union or individual worker comes to us and reports that they’ve been fired because they are HIV-positive, we step in with other NGOs. We set up a meeting with the general manager of the company and the human resources department to make them understand they don’t have to fire a person because that person is HIV-positive. If that person receives proper medical care, they can work for 20 to 30 years without any problems. So, now companies understand that.

VA: Did you notice positive changes regarding people’s behavior now that HIV drugs are available for free?

MTM: There has been improvement since 2001. The fact that drugs are available for free has reduced people’s troubles tremendously. In the past, they were concerned with taking their medication in secret, without being seen by anyone. Even walking into a hospital to get those drugs, people were always afraid of being seen by someone they knew. Currently, they can take their drugs in total discretion because drugs are available everywhere and in every structure. Now, the problem we face is people who have stayed for too long without treatment or who have tried traditional alternative therapies and realized they are not working. At some point, they want to return to their initial medical treatment, so we have to persuade the medical staff to take them back into the normal protocol, despite that they abandoned the initial treatment they were given for months or years.

VA: What improvements have you observed in people having psychological disorders as a result of the stigma imposed by society on those infected by HIV?

MTM: Before, people were depressed and anxious. They were afraid, worried about their families, their jobs, etc. Currently, we observe this less and less.

VA: Like any other disease of this seriousness, it also affects the person’s relatives. Do you do family therapy/training?

MTM: We do a lot of group therapy for both people with HIV and people who have not been infected by HIV. For those with HIV, we group them according to their age. For mature individuals, we do what we call a ‘psychological weekend’. In general, when a person realizes they are not isolated but are among people dealing with the same situation, it helps a lot to lift their mood.

VA: What are your ambitions for your center?

MTM: My center aims to accommodate those affected by HIV and their families during periods of trouble, during times when they struggle to access treatment, or when they are suffering from depression. Helping them as best as I can is my ultimate goal.

...Helping them, helping people as best as I can is my goal.``