09 Jul Anthony Griffin

Photo by Anthony Griffin Photography

Anthony Griffin

A recipient of multiple awards, Anthony Griffin is a Dublin-based photographer who specializes in documentary, portraiture, and event photography. A storyteller at the core, whose work has been published internationally, Griffin conveys insight into the humanity of each of his subjects.

By Victoria Adelaide | July 9. 2018

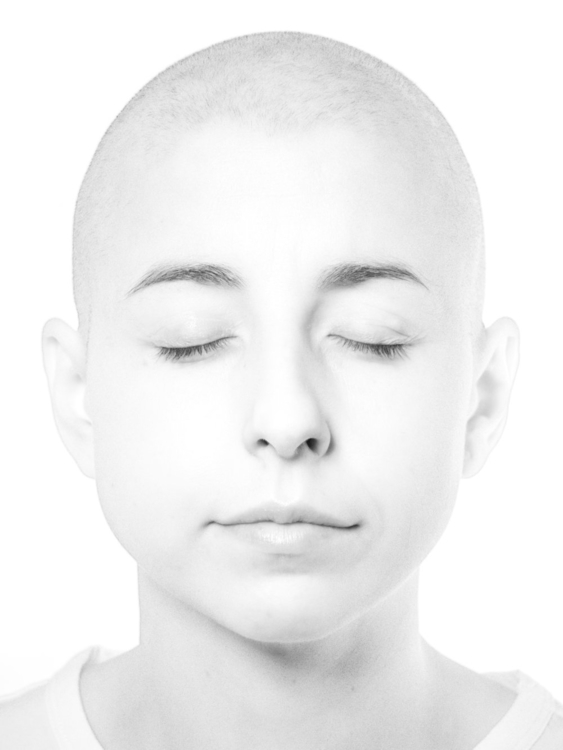

Victoria Adelaide: An Uncommon Beauty is a series of photographs you created on female alopecia. What was it like capturing these women’s images?

Anthony Griffin: An Uncommon Beauty arose from an unexpected conversation I had with a friend. It was a hugely rewarding experience to photograph the women and to hear their stories. In fact, it was a privilege. As Susan Sontag said, “The painter constructs, the photographer discloses.” I feel that is what I did through An Uncommon Beauty. I revealed something that is often hidden. I was quite nervous at the start. I wondered whether I would be able to find enough women that were in a position to participate; however, in the end, I had more than I could continue with. I believe that portraits are collaboration between the photographer and the subject, each placing trust in the other. I felt a lot of responsibility, not only to the women in the project but to the many well-wishers and women around the world that offered to take part. One of the women flew from another country to take part and again for the opening of an exhibition in which my work was shown. She stayed with relatives and learned that she had inherited a serious genetic condition for which she was thankfully treated. She told me that participating in my project might have saved her life. That was a lot to take in. At the very start, I was told I would get more from the project than perhaps the women. In hindsight, I don’t think I would argue with that.

VA: As a photographer, do you think you have a responsibility in the way beauty is perceived by society?

AG: I think photographers have a responsibility outside of the law and standard matters of ethics. We can challenge or be complicit in an unhealthy depiction of idealized beauty. The world is image-saturated and, since its inception, photography has been heading towards the democratization that we see today in this field. A young child can create a recognizable photograph. If we give them a trumpet, paint, a pen, and paper, what they produce will be abstract and indecipherable. Nick Ut’s photo of Phan Thi Kim Phúc in Vietnam through to Nilüfer Demir’s image of Alan Kurdi in Turkey show how mobilizing and influential visual communication can be. Photographers, artists, are often in a position of power, even outside of photojournalism. Thomas Mann claimed that everything is politics. Body image and gender is very much at the front of contemporary discourse and combined with social media and I think we should challenge injustice wherever possible.

Photos by Anthony Griffin Photography.

VA: Your connection with humanity is obvious all over your work, often depicting marginal individuals in their daily dose of struggle or happiness. Do you think that following a certain norm is automatically a validation of normality, if there is normality? And what does normality mean to you?

AG: I’m not sure if normality exists in and of itself or if it is a social construct. I believe as humans, we have an innate reason and tendency for altruism initially stemming from mere survival. I am very interested in people in and outside of my work, of course—how we often simultaneously strive for individuality, acceptance, and approval. I am interested in ‘what makes us tick.’ It’s difficult, for me at least, to consider anything without considering people. Unspoiled areas of natural beauty are notable for the absence of human progress and interference. Even away from our planet, we are looking to build and conquer. Maybe normality, whatever that is, is in the hands of the majority or even the minority to whom they often dictate, shape, divide and, I like to think, often help when it is needed.

VA: Transmission is your project exploring the lives, misconceptions, and assumptions regarding missionary Sisters. What did you learn from them?

AG: This was very much a photo essay-type project and the one thing I definitely learned was that the women were active in human rights and environmental campaigns, long before many of us. They were very progressive women in patriarchal structures who sat, quite literally, on the frontlines, in support of the oppressed. I undertook a series of interviews and, to some surprise, ‘religion proper’ was not the center of the conversations. I had some very enlightening conversations about liberation theology, a kind of hybrid Christian theology and Marxist socio-economics. Their subsequent re-adjustment into civilian life was often very challenging. Much of society was too caught up in their own lives to share an interest with those less fortunate thousands of miles away. Regretfully, this is something that can still be witnessed and observed today. Many of these Sisters moved into non-state education work and environmental causes and tackled issues of social justice in their localities. We hear about the Good Book but, at the heart of this story, was “ Don’t judge a book by its cover”— certainly in relation to the misconceptions or preconceptions of such women.

VA: You studied music at an early age. Do you think that the study of another art form, such as music, shaped your approach to photography?

AG: I first studied the violin, later the clarinet, and then the guitar. I drew from an early age, winning art competitions and later taking on design work. I believe I have always had a creative streak. There are few, if any, professional photographers that I know, who do not have another creative outlet. I also read a lot and spent a few years working for Amnesty International and almost a decade in the community sector. This and other interests shaped my approach to photography. Studying music provided me with an early opportunity to practice and master something. Music is full of dynamics—a word that is featured in photography and is a very personal means of self-expression. A level of sensitivity is required through all creative mediums and artists are generally not afraid to span a variety of outlets.

VA: The Write Words is the incredibly beautiful story of how you met your wife. Do you think romanticism is slowly dying in our highly digital world, where connections are mostly made through the internet?

AG: When we ‘met,’ romanticism was furthest from our minds. We were very honest, as we were writing to someone who we never expected to meet in person. I think we all have to respond to today’s highly digital world regardless of resistance. It’s increasingly difficult to do some things offline, such as banking or finding adequate information. It’s certainly changed how we interact and engage with others. In terms of The Write Words, letter writing is virtually obsolete compared to the recent past. I am still surprised at the number of postcards there are for sale and imagine they are more for souvenirs than posting. People still write but one hears less of beautiful handwriting. I just can’t imagine seeing emails in museums. More than a decade ago, Warwick University’s Cybernetic Culture Research Unit claimed that children growing up using mobile phones and gaming consoles are changing the shape and dexterity of their fingers and thumbs. If you use your index finger and not your thumb to ring a doorbell, you know where to place yourself. We’re bombarded with information and disinformation and I think the lack of investment in time and honesty is one of the worst sides of digital connections.

VA: How would you like people to think of you as an artist/person?

AG: As imperfect as I am, that I was a good person and good company. In truth, I’m not sure anything else matters. I have friends for whom all I can do is remember them and when I do, consciously and deliberately, I remember the goodness, their company, their talents, and their legacy. I lost a friend to cancer a little over a year ago and I think of him as I would have liked him and others to think of me. He was one-of-a-kind and that’s about the best epitaph I can think of. For the moment, until my own epitaph is written, I’ll settle on being thought of as the result of who I am and what I do today.

...I believe as humans, we have an innate reason and tendency for altruism..``