15 Oct Réhahn

Photo by Réhahn

Réhahn

French photographer, Réhahn, also known as the photographer who captures the soul of his models, has traveled to over 35 countries before settling in Vietnam. Ranked as the second most popular French photographer on the internet and the recipient of various accolades and honors, Réhahn gained global recognition a few years ago with his portraits of Vietnam, India, and Cuba. A savvy businessman and owner of several galleries and museums in Vietnam, Réhahn is the founder of the Precious Heritage Museum, which is aimed at preserving and promoting the heritage of ethnic groups whose culture might soon be lost forever. Highly concerned by the human condition, Réhahn is the mind behind the Giving Back Project and one of the very few photographers in the world who uses their art as a medium to alleviate poverty and human suffering.

By Victoria Adelaide | Oct 15. 2018

Victoria Adelaide: Why Vietnam?

Réhahn: First, I’d like to say it was the opposite of many of my other trips—it’s not photography that took me to Vietnam. In September 2007, I decided to sponsor a little girl from Hội An, Vietnam, where I currently live. Two months later, with the help of the humanitarian association we were involved with for the sponsorship, my wife and I went to Hội An for the first time to meet the little girl. We ended up spending four days with her and her big sister. At the time, they were 7 and 13, respectively. At first, it wasn’t easy because they couldn’t speak English and we couldn’t speak Vietnamese. Luckily, we met a nice young woman working in a store. She became a friend and she invited us to stay during those four days so she could help us with the translation. So, we spent most of those four days in that clothing store, but we could finally communicate with the girls. On the fourth and final day, we were all a bit emotional. We laughed so much, ate together, and we started feeling really connected to those little girls. They asked us if we would come back to see them and we promised we would. Nine months later, we went back to Hội An and spent 15 days with them. From then on, we went back every year up to 2011, when we decided to settle there to be with them rather than to bring them to France or adopt them. Therefore, in a way, I could say they adopted us and they truly are like my daughters. That’s how we settled in Hội An.

Photo courtesy of Réhahn.

VA: You seem very sensitive to people’s kindness over there. Do you think the West has lost it all?

R: I was very opinionated about France when I left. I thought I would never return. However, years have passed and I’ve learned that the world is not just black and white—we can’t just put everybody in the same bag because there are still a lot of great people out there. I think that even if France is considered one of the most developed countries, we have become so underdeveloped when it comes to human emotion, the way we interact with each other, and the empathy we seem incapable of developing for one another. Just watching all those people ready to queue four hours from five o’clock in the morning in front of an Apple store just to get the latest iPhone is insane. And those same people would avert their gaze from a person in real need. When I look at my father, he has friends he’s known for 40 years. Now we don’t keep friends for more than five years, because, at the first argument, we stop communicating with each other. The same thing applies to love. In Vietnam, because grandmothers take care of the children, they are not sent to retirement homes and children don’t need to stay in nurseries. Young Vietnamese use their salary to support their family. As a result, the core of the family is strong. Also, the Vietnamese are proud to befriend or have foreigners in their schools or in their homes, because they are genuinely interested in meeting and learning from foreigners—it’s in their nature. Sometimes, I travel to villages and people start cooking dinner for me before I have time to tell them I can’t stay and I inevitably end up having dinner with them because they are just genuinely happy to have me at their table. In France, we have become suspicious. We have big dogs, we lock up ourselves at home, and we might not speak to an old lady because we are too afraid she might think we’re going to steal her bag. Each foreigner is seen as a potential threat. You compliment a woman and you become a pervert, etc. It wasn’t like that in the past but France has become this suspicious microcosm. It’s a new normality and I don’t like it very much.

VA: You focus on portrait photography. Why?

R: My main inspiration is humans—that’s why I’m so interested in portraits. A portrait goes beyond this notion of what’s aesthetic—there’s wrinkles, a look, a smile. Of course, I appreciate a beautiful landscape but it’s never going to be as exciting to me as portraits are. When I look at a portrait, I can still hear the person laughing. When I have the picture in front of me, I remember what they told me, the sound of their voice, their fears, and their life story. I’m interested in the picture’s story and, obviously, the next logical move was to tell stories. That’s how I naturally came to the ethnic groups’ project. I also like lifestyle pictures that represent tradition. My focus is not on the technique or the aesthetic aspect of it but to immortalize a tradition and a culture that may no longer exist in a few years.

Photos by Réhahn.

VA: Do you see yourself as a storyteller?

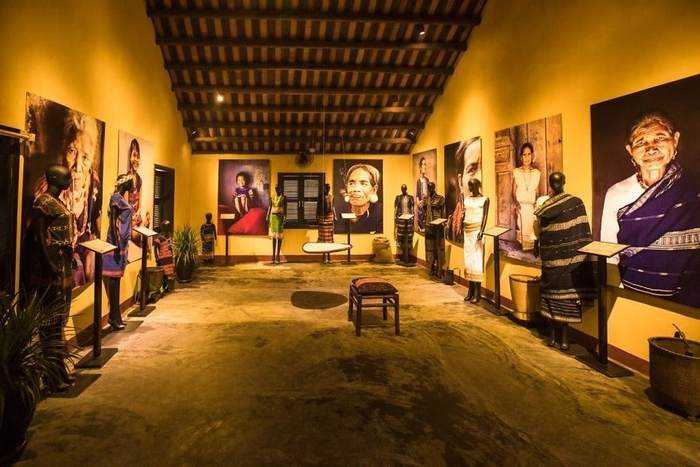

R: Absolutely. The picture tells a story in itself. I wrote these stories and created a free museum to have them on display. So far, I’ve met 49 ethnic groups out of 54. I met the smallest ethnic group in Vietnam; it consisted of 376 people. Now I have this museum of 500 square meters that I opened in January 2017, seven years after the launch of my project on ethnic groups. It took me a while to gather everything. I looked for those groups from the north to the south, all over the country. Further, to access those remote regions, I need a permit and that can take a very long time to get, years sometimes. This museum is in English, French, and Vietnamese to give Vietnamese people the opportunity to discover their own culture because they do not know anything about those ethnic groups—they are not taught about them in school. I kept the traditional costumes I was given generally by the chief of the village. They are on display in the museum and the manufacturing process was well documented. Vietnam gave me a new life and this museum is my way of giving back to the Vietnamese people and to the country. That’s why I called it the Precious Heritage Museum.

VA: You are the instigator of the Giving Back Project, which works in concert with the Precious Heritage Museum. Can you tell us a bit about it?

R: I needed to finance the Precious Heritage Museum, so I sold my pictures as limited editions with prices that would increase as the collection decreased. I managed to sell pictures valued up to $50000 and, as a result, I could finance my museum without having to ask for money from the government or various foundations. Now that the financing of the museum is finished, I decided to finance another museum of 600 square meters for an ethnic group I like very much. I feel the group is not present enough at the Vietnam Museum of Ethnology. I feel they deserve a museum just for them, and that is the Giving Back Project. Basically, I give back to communities and individually to the models in my pictures. With the Giving Back Project, I can impact their lives consistently by simply asking them what they really need. I bought veal for some families, a boat for a grandmother, I pay for school for all the children who are in my pictures, etc. It’s also a great reason for me to go visit them on a regular basis because they are like family to me.

VA: What are you working on? Do you also have two new galleries?

R: I have one gallery in Hội An and one in Ho Chi Minh City. These galleries financed the Precious Heritage Museum and the Ho Chi Minh gallery truly helped finalize the financing. I thought if I open a new gallery, I could sell more and open a new museum for the ethnic group, which is the Giving Back Project. So, this and next year, all my earnings will go into financing this new museum I’m building in an ethnic village. It’s not a touristic museum; it’s more like a museum of preservation of culture. So, when the young generation starts searching for answers, they will have the possibility of finding answers there. By developing more and more galleries, I can create more museums for other ethnic groups. I opened a new gallery at the Intercontinental Hotel in Ho Chi Minh City on October 1st and I recently bought a new building in Hội An where I plan to relocate my first Hội An gallery on December 1st.

VA: Any last words?

R: There’s a quote from Nietzsche that I love: “Become who you are.” I feel I found myself the day I came to live in Vietnam.

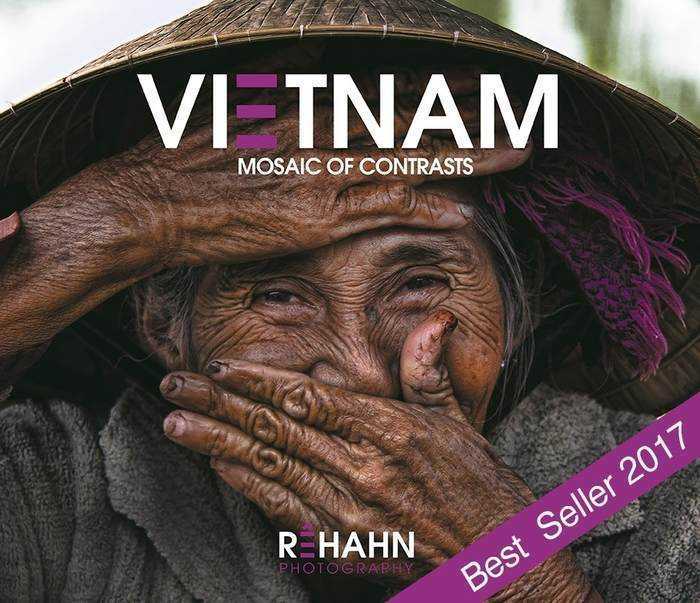

BOOKS | ORDER YOUR COPY

THE PRECIOUS HERITAGE MUSEUM | VISIT NOW

...I found myself the day I came to live in Vietnam.``